How China cast its light on the west

Reports about China that Jesuit missionaries sent home had a profound influence in court and intellectual circles of Europe

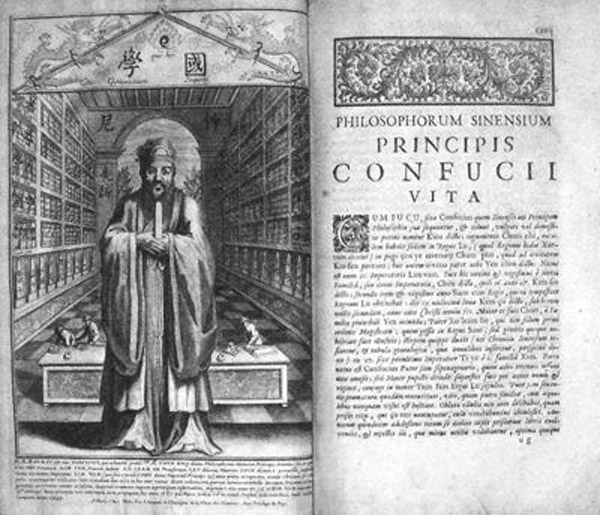

In 1658 Martino Martini, an Italian Jesuit missionary who had spent time in China, published in Munich one of his four influential books about the country. Sinicae Historiae Decas Prima tells the history of China starting from antiquity and ending at 1BC, a year that falls under the reign of Emperor Aidi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24).

Trying to incorporate Chinese history into the system and chronology of European history telling, Martini, who was preoccupied with converting people, failed to gauge the impact his works would have on intellectuals in the West.

"It contradicts or even undermines the Bible," says Zhang Xiping, a leading scholar on cultural exchanges between China and the West.

"While identifying Fuxi as the first emperor in primordial China, Martini also noted that the coming to power of Fuxi took place 600 years before Noah's Ark was spared by God in the world-engulfing flood, as depicted in the Old Testament.

"And it became apparent that the birth of Jesus, which most scholars today believe to have been around the beginning of the first century, echoes China's Western Han Dynasty, an era marked by rapid social development and flourishing culture."

Voltaire, the French writer and philosopher who played a central role in defining the 18th-century Enlightenment, is believed to have been deeply impressed - and shocked - by the book. "What about if what Martini wrote is true?" Voltaire is believed to have said. "Then what should I do with the Bible?"

That question has no doubt taken Voltaire and those who came after him forever to answer.