Wellington Koo: the man who stood up for China

Editor's note: In June 1945, China joined the United Nations as one of its founding members. Almost 75 years later, China Daily looks back at the remarkable life of V.K. Wellington Koo, a man who tapped into the power of diplomacy in service of his beloved country.

Back in the very beginning of the 20th century, a teenage Chinese boy went to a barber's shop to have his queue braid cut. The barber, who agreed to take up the scissors only after having repeatedly confirmed with his young client about his bold decision, charged him double. The boy wrapped his queue in a ribbon and took it home to his mother, and the mother cried.

The boy was Koo Vi-kyuin (Gu Weijun), more famously known as V.K. Wellington Koo, viewed today by many as the first truly modern Chinese diplomat to have stepped onto the international stage representing the world's most populous country.

In retrospect, the cutting of the queue provided a potent metaphor for Koo's life, in which he tried very hard to break loose of the constraints imposed on him by family and tradition.

Right after his daring hair move, Koo went on to find himself a set of Western suits and sported them as he appeared in a family photo with his father and two elder brothers, standing symbolically away from the cheongsam-donning three.

However, one thing was never up for severing, and that is the tie between Koo and his country. In 1904, the 16-year-old boarded a ship for the United States, where he first entered the Cook Academy in New York and then Columbia University.

Shirley Young became Koo's stepdaughter when her mother, Juliana Yen Yu-ying (Yan Youyun) married Koo in 1959. Today, the 83-year-old is able to reconstruct her stepfather's Columbia years by looking into the school records, including test sheets.

"There were a number of C's and D's, especially in his first year," she said. "Koo was never this Chinese nerd who just studied hard — he was extremely active in all extra-curriculum activities. These included joining the drama club, becoming the editor-in-chief of the University's Spectator Magazine, which is still in existence today, and leading Columbia's debate team against Harvard, Yale and Princeton.

"I have all the records of the debates — they won so many times that Koo was personally congratulated by the president of the university," Young continued. "Can you imagine that this was for a Chinese person with English being his second language?"

Formidable linguistic capability — Koo would be tapping into this natural endowment in the coming years as he spoke for China on such occasions as the Paris Peace Conference and the San Francisco Conference. But back at Columbia, he had another reality to grapple with.

"Koo came with his first wife, the daughter of a family friend whom Koo had agreed to marry only when his father went on a hunger strike," said Young. "But the marriage was never consummated, according to Koo, who put his new wife in a boardinghouse while he studied at Columbia."

Nationwide revolution broke out in China in October 1911, resulting in the overthrowing of the Qing Dynasty early the next year. An empire no more — China was finally a republic.

In February 1912, a letter from the Chinese embassy in Washington landed on Koo's desk. It was an invitation to serve in the President's Office as his English secretary.

By late 1915, Koo was already appointed the Chinese minister to the US. He was only 27. The year before, he married Tang Pao-yueh (Tang Baoyue), aka May Tang, daughter of veteran politician Tang Shaoyi, after finally obtaining a divorce from his first wife the previous year.

The second marriage, a happy one, ended abruptly three years later, as Tang died in the influenza epidemic of 1918 in the US, having borne Koo a son and a daughter. Many years later, that daughter, Patricia Tsien, born one year before her mother's passing, would tell her own daughter, Ying-Ying Yuan, about going back to China with Koo at the age of 5, for her mother's burial 4 years after her death. Both Tsien and Yuan later became the guardians of Koo's legacy.

Back in 1918, Koo had little time to grieve. In January 1919, he was appointed one of China's five plenipotentiaries to the Paris Peace Conference, where the victorious Allied Powers gathered following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers.

China, which had seen its rights as a sovereign country repeatedly infringed on since the mid-19th century, was within the Allied camp.

One focal point concerned the disposal of the leased territory and other rights previously held by Germany in East China's Shandong province, things that had been "wrung out of China by force", to use the words of Koo. In the beginning of World War I, Japan, which had long been eyeing this strategically important piece of land, declared war on Germany, won, and became the land's de facto occupier.

Facing Japan's attempt to have the German rights and interests "legally" transferred to them during the meeting, Koo fought fervently, basing his argument squarely on his study of international law at Columbia.

"The territories in question were an integral part of China. They were a part of a province containing 36 million inhabitants, of Chinese in race, language and religion. … On the principles of nationality and of territorial integrity, principles accepted by the Conference, China had a right to the restoration of those territories. The Chinese delegation would feel that this was one of the conditions of a just peace," he said. "If, on the other hand, the Congress were to take a different view and were to transfer these territories to any power, it would, in the eyes of the Chinese delegation, be adding one wrong to another."

In order to strike a chord with representatives from the West, Koo went on to say that to ask the Chinese to willingly give up Shandong, the home province of Confucius, was akin to asking the Christians to abandon Jerusalem.

Well deliberated and forcibly delivered, the speech was a big success — US President Woodrow Wilson walked up to Koo and congratulated him on the spot. (The president had previously invited Koo to his wedding to Edith Bolling Galt.)

That history was powerfully reenacted in the 1999 Chinese movie My 1919, with veteran Chinese actor Chen Daoming impersonating Koo. However, as the diplomat later noted, "it was one thing to make an impressive speech yet quite another to receive a favorable resolution". Japan threatened to walk away from the meeting and render all its decisions ineffective. The Allied Powers, eager to solidify their own interests, folded.

"I made it clear that China had no choice but to refuse signing," recalled Koo in his memoir.

According to Young, although a telegram from Beijing did arrive later telling them not to sign, Koo was most likely to have arrived at that decision independently, with another young man in the delegation.

"Some more senior members had left, and it was up to them, the bottom guy and next-to-the bottom guy, to fulfill their last-minute duty," she said, reflecting on the fact that Koo's famous speech at the conference was delivered only when an impromptu decision was made for him to replace another member of the group for the occasion.

Back home, China's failure at the peace conference was met with immense disillusionment and outrage, moods palpably felt even in Paris.

"When members of the delegation came out of their residence in the suburb of Paris, they were confronted by some emotional Chinese students, among whom was Zheng Yuxiu, who at that point declared that she had a gun in her coat," said Young.

"Many years later, Zheng as a social friend of us came to dinner at our house. Koo asked, 'Did you really have a gun?' She said, 'No, it was a stick.' Koo smiled and said, 'I thought so'," Young recalled.

It took many years before they could laugh at certain aspects of the incident. Back then, the pain was acute. And China, fought over by its warlords, slid further into darkness.

In July 1928, the Chinese Nationalist Party completed its military campaign known as the Northern Expedition and toppled the incumbent warlord government. Koo, who had acted as foreigner minister, finance minister and even interim premier and president under various warlords, was initially put on the "wanted" list but was later invited to work for the new government.

It was only three years before Japan's incursion into the northeastern part of China known as Manchuria and nine years before the Chinese war against Japanese aggression officially broke out on July 7, 1937.

For most of World War II, Koo, who had appealed to the international community over the Japanese invasion, served as the Chinese ambassador to Britain. "His big job was to get help from the rest of the world for the Chinese position against Japan," said Young, who recalls Koo arriving at Winston Churchill's residence for a meeting in the afternoon, when the latter was "coming downstairs famously dressed in his pajamas".

According to Young, at certain points during the many meetings they had throughout the war, Koo raised with the British prime minister the issue of Hong Kong, having gained support from President Roosevelt on it. "Churchill said something like 'In principal I agree, but let's wait until the end of the war'," Young said.

Many years later, when Koo, having been long retired and living in New York, read in a local newspaper that a date was finally set for Hong Kong's return to China, he carefully cut that piece out.

Throughout those warring decades, Koo had by his side "a strong and talented woman" — to use the words of Yuan the granddaughter — whom he married in 1921 and whom Yuan described as "a major contributor to my grandfather's diplomatic career".

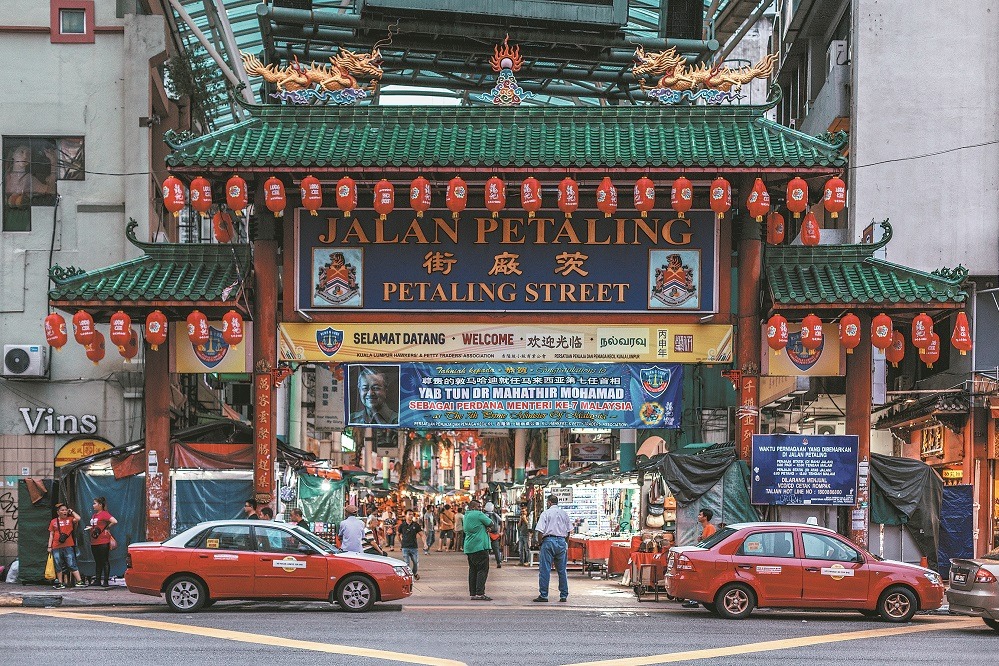

Daughter of Oei Tiong Ham, a Chinese Malaysian businessman and arguably the wealthiest person in the Far East at the start of the 20th century, Oei Hui-lan (Huang Huilan) spoke six languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Chinese and Malay.

"Her linguistic abilities matched his," said Yuan, referring to Koo's mastery of English and French on top of his native Chinese. "She's a modern diplomat's wife who could not only entertain guests from different cultural backgrounds but also give speeches in a foreign country, on behalf of China to which she was just as committed."

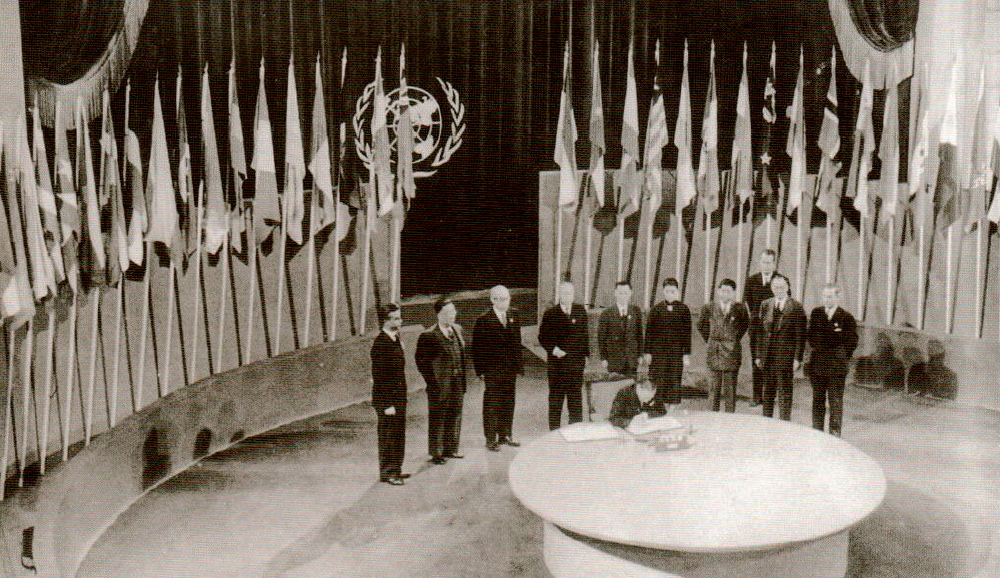

On June 26, 1945, while the bloody fighting of World War II was finally drawing to a close, Koo led an eight-person Chinese delegation at the signing of the United Nations Charter at the Herbst Theater in San Francisco.

"Wellington Koo was the first person to sign because alphabetically China was the first country. It was on the front page of the newspaper that people brought to me in the hospital ward," recalled Young, who at the time was recovering from appendicitis, which she suffered shortly after her arrival in San Francisco from the Philippines, accompanied by her mother and two sisters.

Young's father, Clarence Kuangson Young (Yang Guangsheng) had served as the Chinese consul general in Manila between 1938 and 1942, before his secret execution by the Japanese in April that year. Not knowing what had happened to her husband until the end of the war, Young's mother, known at the time as Juliana Young, managed to take care of her own family — as well as those over-30 widows and children of the consulate staff who had come to share the three-bedroom bungalow house with her and her three young daughters — through the darkest days.

Looking back to that historic moment, Shirley Young calls "getting China on the UN Security Council" Koo's "big, big long-term contribution, one that's still very much relevant today".

"When people see success, they don't know what went on before: along the way China was continuously not invited to meetings, cut out of things, not given a seat," she said.

One example was the Dumbarton Oaks Conference held in Washington DC, formally known as the Washington Conference on International Peace and Security Organization. It was at this conference that the United Nations was formulated and negotiated among international leaders. The fact that China was excluded from the main body of the conference led Koo, who was there representing China, to describe it as "a step backward" for his country.

With that in mind, it seemed highly unlikely if not illogical that China would be able to sign in as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council merely 10 months later, at the San Francisco Conference, or the United Nations Conference on International Organization. Young believed that's where "diplomacy was evident".

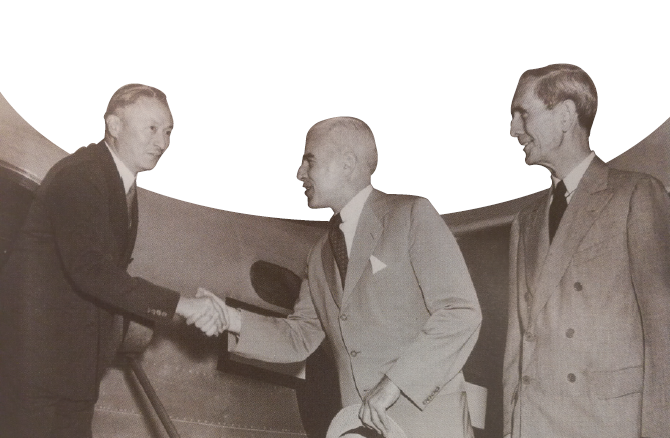

"All previous setbacks aside, Koo remained optimistic, and kept on working with America, England and France," said Young, who called Koo "a great relationship person" whose friendship with President Roosevelt went back to the days when Roosevelt was an assistant secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration and Koo himself the Chinese minister to Washington.

"He networked not just with Roosevelt, but a lot of people underneath — the secretary of state, the entire state department, etc — to build good, trusting relationships," said Young. "He showed people that he could help them get what they wanted. But in return, they needed to support what he had envisioned for China."

Having done research into Koo's life over the past three decades, Jin Guangyao from Shanghai's Fudan University lauded Koo's perseverance and foresightedness. (It's worth noting that Juliana Young, who later married Koo, was among the first group of female students enrolled at the university, in the late 1920s.)

"Koo insisted that China send her own delegation to the Dumbarton Oaks Conference despite any possible sidelining during the event, with the clear goal of making China one of the 'Big Four' (The others were the US, UK and Soviet Union)," he said. "He did accomplish that, when China became one of the four signers for the papers issued by the end of the conference in regard to the founding of the UN. This effectively laid the basis for China's future role at the international organization.

"But of course, an evaluation of Koo's effort must be put into the bigger context of what was happening in the China theater of the war, where hard-won victories by the Chinese Army against fascist Japan had certainly served to greatly elevate the country's international status," he said.

The history professor saw a clear strategy consistently followed by Koo as a diplomat. "Allying with the United States against Japan — that was what Koo had formulated and championed in the '20s and '30s, before finally putting it into practice in the '40s during WWII," Jin said. "Koo saw Japan as China's biggest enemy as far back as 1915, when the former imposed on China its Twenty-One Demands aimed at establishing sole control over Chinese territory.

"And he believed that to 'engage with the distant US … would be sufficient to contain an approaching, menacing Japan'," Jin continued, quoting Koo's own words. "It's fair to say that as a member of the US-educated elite, Wellington Koo played an important role in shaping US-China policy for more than two decades."

In the years after World War II, Koo acted first as the Nationalist government's ambassador to the US, and then after the founding of the People's Republic of China on the Chinese mainland in 1949, continued to represent in Washington the government in Taiwan until his retirement in 1956. Also in that year, Koo divorced his third wife Oei Hui-lan.

For the three years between 1946 and 1949, when the Communists and the Nationalists fought the Chinese Civil War, Koo had been trying actively to draw American support for the latter, but to little avail, as the American confidence in Chiang Kai-shek and his government flagged.

On Oct 25, 1971, the United Nations General Assembly voted to admit the People's Republic of China and to expel the Republic of China (Taiwan). The PRC therefore assumed Taiwan's place in the General Assembly as well as its place as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. On Jan 1, 1979, China and the US officially established diplomatic ties.

Reflecting on Koo's political stance, Young, the stepdaughter, said that he was "China oriented instead of party oriented". "I believe that his major concern during the civil war years was that China was being split up. And this is something he had spent his entire career preventing from happening," she said.

"Koo almost never talked about the historic events in his life," said Young. "When we were together, it's just really all family talk. But one thing he always said — I heard this many, many times — was that 'wo shi yi ge wu dang wu pai zhong guo ren', meaning 'I'm a non-partisan Chinese.'

"If you looked at his record throughout the 1920s, he had never ever participated in those internecine battles of the warlords," continued Young. "He never joined any of them but whoever seized power came back to him. He started to work for the Nationalist government around 1929, but was only compelled to join in 1941, when he was appointed the Chinese ambassador to Britain. Why? Because per usual diplomatic convention, the appointment of an ambassador required the approval of the British government, which thought it would be better for the Chinese government to appoint a Nationalist party member."

In 1945, Koo was responsible for providing a list of candidates whom he would then lead to the San Francisco Conference. Among others, Koo recommended Tung Pi-wu (Dong Biwu), a veteran Communist. "I believed that there was no one line of political thought which could be absolutely right to the exclusion of others," he later said in the oral history project he did with Columbia University, his alma mater.

According to Young, Koo, who had never lived in Taiwan, was invited to return to Chinese mainland when Zhang Hanzhi, Mao Zedong's English teacher and a young diplomat, visited him in New York in 1972.

"Age, health and Grandma Juliana — that's the three main factors for him deciding not to go back," said Yuan, the granddaughter. "But he found a representative in my mother, who first went to the Chinese mainland with my father in 1972, a trip followed by others over the years. Every time she went, she went back to talk with Grandpa about what she saw."

Koo and Juliana Young, who had been working at the UN between 1946 and 1959, married in 1959, three years after Koo's divorce from Oei. The couple lived in The Hague between 1957-67, when Koo was elected a judge on the International Court of Justice, before retiring as its vice-president and moving permanently to New York.

Yuan credited "Grandma Juliana" for taking good care of her grandfather during the 17 years between 1959 and 1976, when Koo, working with 5 scholar interviewers, recorded 500 hours of spoken memoirs as a Columbia University oral history project.

"It was very intense, and everything was done in English," said Yuan, whose mother, Patricia Tsien, later started another gigantic project lasting for 13 years, to translate Koo's oral history into Chinese. The result was more than 6 million characters.

"After initially being contacted by someone from the Chinese mainland, my mother, with approval from my grandfather, worked with a big group of translators based in Beijing and the neighboring Tianjin city — there were about 34 of them in total," Yuan continued. "She went to China to meet everyone of the group, who later wrote constantly to her asking all sort of questions like 'What is this person's Chinese name?' and 'Where was Mr Koo exactly at this time?'"

"With oral history, there can be gaps, gaps that my mother worked very hard for many, many years to fill," said Yuan, a Harvard-educated anthropologist who herself helped with researching and fact-checking. "Let's not forget that this was in the late '70s and '80s, with China still being a very politically sensitive place. To push ahead with such a project required a lot of foresight from our partners on the mainland."

Along the way, pictures were collected and part of them eventually went to the memorial museum for Koo in the Jiading District of Shanghai, where he was born in 1888.

Tsien passed away in 2015, at age 97, pleased with the fact that her father was able to see the very first of the 13-volume translation before his own passing, also at the age of 97, in 1985.

Both Yuan and Young have become the torch bearers for Koo's legacy over the years.

After Koo's passing, Young, together with her mother, donated to the memorial museum the cases of books from his bedroom, books in which Koo "circled things".

"Koo kept everything, including a thank-you note I wrote him at age 11, after receiving a box of chocolates he sent to me," said Young. "All those records were given to Columbia and put into their Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the end of the oral history project.

"Four years ago, I brought Columbia and a number of Chinese institutions together, in an effort to digitalize the materials and make them available to researchers in China," said Young, who described Koo's marriage with her mother as "one of great affection and devotion" and Koo himself as "fun-loving".

"He took up skiing in his early 70s, get himself on the Time magazine page before getting my mother to ski with him. And that was before he accidentally fell off and hurt his shoulder while we skied in Austria. He was trying to show off to my mother," recalled Young, laughing. On the day of the interview, she was wearing a seal-shaped jadeite given to her mother by Koo as a gift.

"Every night, my mother would put a glass of Ovaltine, which is a chocolate milk drink, outside his room, in the hallway. And then the next morning, she would check to make sure that he had drunk it — he would usually get up at around midnight after he went to bed."

V.K. Wellington Koo died peacefully on Nov 14, 1985, and was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum in Hartsdale, New York. There was a diary entry that day in the morning. It says, "A quiet day."

Juliana Young Koo, as she signed her name on the cover of her autobiography 109 Springtimes — My Story, published in 2015, passed away in 2017, at the age of 111.

Oei Hui-lan, known by her friends as Madam Koo, died in 1992 at the age of 100. Her autobiography, published in the 70s, is titled No Feast Lasts Forever.

On June 28, 1919, the very last day of the Paris Peace Conference, Koo, having decided not to turn up and sign, "drove slowly in the morning twilight".

"Everything looked so sad to me — the color of the sky, the shade of the trees and the deserted streets. I thought the day must remain in the history of China as the day of sorrow," he wrote in his diary.

Young, who organized a memorial concert for Koo at New York's Carnegie Hall last year, understands all that.

"If he died in his 60s or 70s, he might have felt a sense of failure. But he lived a long life, which allowed him to take great comfort in the fact that China was finally on its way to become a major world power. Koo was a true globalist with a distinct vision for China in the global community," said Young.

As vice-president of General Motors, Young was responsible for the project between her company and the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corp (now SAIC Motor) in the 1990s, a landmark initiative that not only "saved General Motors" but also "helped China to build its own modern auto industry".

"When I graduated from college in the early '60s, I had no country to go into a diplomatic career for — not American, and China was closed. … What I ended up doing is a form of economic diplomacy," said Young, who co-founded the Committee of 100 with such prominent Chinese Americans as the late architect I.M. Pei and master cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

The committee, whose members are "American citizens of Chinese heritage", is dedicated to advancing dialogue at various levels between the US and China.

Appearing at the memorial concert in New York, Chinese Consul General Huang Ping called Koo's achievements "difficult for us to reach". "These books (his 13-volume oral history) are must-reads for Chinese diplomats," he said.

Huang's words were echoed by Max Baucus, the former US ambassador to China, when the latter, attending the opening of Koo's redesigned memorial museum in December 2018, pulled out his mobile to take a picture of a Koo quote printed on the wall.

"In foreign affairs, one should aim for 51 percent of his goals and should be quite happy with 60 percent or more," the quote goes.

Yet the materialization of that humble 51 percent demands a 100 percent input, as Koo's career has demonstrated.

Back in the late 1890s, Koo was passing a bridge over the Huangpu River in Shanghai when he saw a plump Englishman whipped a rickshaw puller, despite all the difficulty the Chinese was having pulling the cart up slope against the wind.

At a time and a place where, to use Young's words, "foreigners were king", the teenage boy stood in the wind on the sidewalk and shouted to the man what must be the biggest insult he could possibly thought about — "Are you a gentleman?"

"It was too much for a boy of that age to understand political reforms, but I could feel that something was wrong and needed to be corrected," wrote Koo, who years later would argue on a world stage for China to take back the concessions and abolish all unequal treaties. "I made up my mind to be a diplomat."