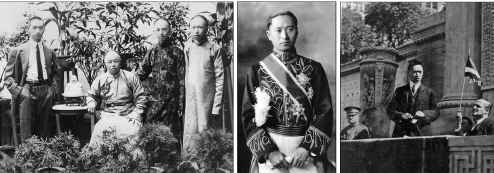

Wellington Koo: The man who stood up for China

He is viewed by many as China's first modern diplomat, Zhao Xu reports.

"Many years later, Zheng as a social friend of us came to dinner at our house. Koo asked, 'Did you really have a gun?' She said, 'No, it was a stick.' Koo smiled and said, 'I thought so'," Young recalled.

It took many years before they could laugh at certain aspects of the incident. Back then, the pain was acute. And China, fought over by its warlords, slid further into darkness.

In July 1928, the Chinese Nationalist Party completed its military campaign known as the Northern Expedition and toppled the incumbent warlord government. Koo, who had acted as foreigner minister, finance minister and even interim premier and president under various warlords, was initially put on the "wanted" list but was later invited to work for the new government.

It was only three years before Japan's incursion into the northeastern part of China known as Manchuria and nine years before the Chinese and Japan officially went to war on July 7, 1937.

For most of World War II, Koo, who had appealed to the international community over the Japanese invasion, served as the Chinese ambassador to Britain. "His big job was to get help from the rest of the world for the Chinese position against Japan," said Young, who recalls Koo arriving at Winston Churchill's residence for a meeting in the afternoon, when the latter was "coming downstairs famously dressed in his pajamas".

Throughout those warring decades, Koo had by his side "a strong and talented woman"-to use the words of Yuan the granddaughter-whom he married in 1921 and whom Yuan described as "a major contributor to my grandfather's diplomatic career".

Daughter of Oei Tiong Ham, a Chinese Malaysian businessman and arguably the wealthiest person in the Far East at the start of the 20th century, Oei Hui-lan (Huang Huilan) spoke six languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Chinese and Malay.

"Her linguistic abilities matched his," said Yuan, referring to Koo's mastery of English and French on top of his native Chinese. "She's a modern diplomat's wife who could not only entertain guests from different cultural backgrounds but also give speeches in a foreign country, on behalf of China to which she was just as committed."

On June 26, 1945, while the bloody fighting of World War II was finally drawing to a close, Koo led an eight-person Chinese delegation at the signing of the United Nations Charter at the Herbst Theater in San Francisco.

"Wellington Koo was the first person to sign because alphabetically China was the first country. It was on the front page of the newspaper that people brought to me in the hospital ward," recalled Young, who at the time was recovering from appendicitis, which she suffered shortly after her arrival in San Francisco from the Philippines, accompanied by her mother and two sisters.

Young's father, Clarence Kuangson Young (Yang Guangsheng) had served as the Chinese consul general in Manila between 1938 and 1942, before his secret execution by the Japanese in April that year. Not knowing what had happened to her husband until the end of the war, Young's mother, known at the time as Juliana Young, managed to take care of her own family-as well as those over-30 widows and children of the consulate staff who had come to share the three-bedroom bungalow house with her and her three young daughters-through the darkest days.

Looking back to that historic moment, Shirley Young calls "getting China on the UN Security Council" Koo's "big, big long-term contribution, one that's still very much relevant today".

"When people see success, they don't know what went on before: along the way China was continuously not invited to meetings, cut out of things, not given a seat," she said.

One example was the Dumbarton Oaks Conference held between August and October 1944 in Washington DC, where the United Nations was formulated and negotiated among international leaders. The fact that China was excluded from the main body of the conference led Koo, who was there representing China, to describe it as "a step backward" for his country.

With that in mind, it seemed highly unlikely if not illogical that China would be able to sign in as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council merely 10 months later, at the San Francisco Conference, or the United Nations Conference on International Organization. Young believed that's where "diplomacy was evident".

"All previous setbacks aside, Koo remained optimistic, and kept on working with America, England and France," said Young, who called Koo "a great relationship person" whose friendship with President Roosevelt went back to the days when Roosevelt was an assistant secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration and Koo himself the Chinese minister to Washington.

"He networked not just with Roosevelt, but a lot of people underneath to build good, trusting relationships," said Young. "He showed people that he could help them get what they wanted. But in return, they needed to support what he had envisioned for China."

History professor Jin Guangyao from Shanghai's Fudan University have researched into Koo's life over the past three decades. "Koo insisted that China send her own delegation to the Dumbarton Oaks Conference despite any possible sidelining during the event, with the clear goal of making China one of the 'Big Four' (The others were the US, UK and Soviet Union)," he said. "He did accomplish that, when China became one of the four signers for the papers issued by the end of the conference in regard to the founding of the UN. This effectively laid the basis for China's future role at the international organization.

"But of course, an evaluation of Koo's effort must be put into the bigger context of what was happening in the China theater of the war, where hard-won victories by the Chinese Army against fascist Japan had certainly served to greatly elevate the country's international status," he said.

Jin saw a clear strategy consistently followed by Koo as a diplomat. "Allying with the United States against Japan-that was what Koo had formulated and championed in the '20s and '30s, before finally putting it into practice in the '40s during WWII," he said.