Virologists cast doubt on vaccine efficacy

Virologists have called into question the efficacy of a novel coronavirus vaccine being developed by a United Kingdom pharmaceutical company and researchers at Oxford University.

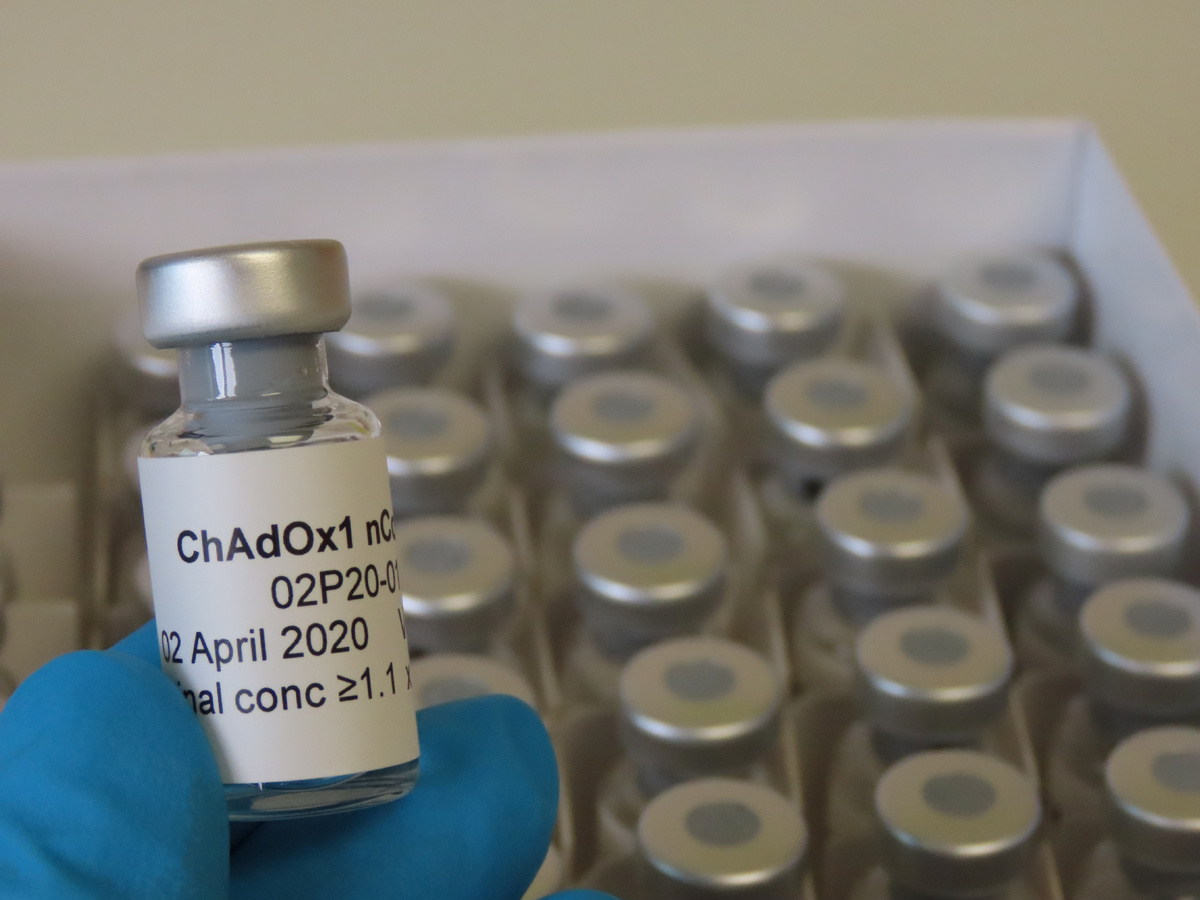

The vaccine, known as ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or more commonly the Oxford vaccine, is currently undergoing clinical trials in humans and has received large amounts of government funding from both the UK and the United States.

The Jenner Institute and Oxford Vaccine Group-both at the University of Oxford-are collaborating on the vaccine alongside Cambridge-based pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, which will manufacture and distribute the treatment.

The Oxford vaccine has been touted as one of the most promising inoculations for the novel coronavirus-caused COVID-19 disease currently in development. On Thursday, the US Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, which is a subsidiary of the US Health Department, provided the developers with $1 billion in funding under the expectation that AstraZeneca will deliver 300 million doses to the US by October.

On Sunday, the UK government confirmed it had invested 65.5 million pounds ($80 million) in the vaccine project as part of an agreement to make 30 million doses available by September.

But some virologists have concerns about the vaccine, particularly stemming from earlier trials in rhesus monkeys, for which results were released on May 13. William Haseltine, a former professor at Harvard Medical School and renowned HIV specialist, wrote in a Forbes blog post on Saturday that the study provides evidence to the effect that, while the vaccine was found to moderate COVID-19 in monkeys, it did not protect the animals from infection.

Jonathan Ball, a professor of virology at the University of Nottingham, told China Daily that, if the same results displayed in the monkey trials are seen in humans, then there is a chance that people who are vaccinated could still become infected and spread the virus.

"The fact that the vaccine prevented pneumonia in all, and symptoms in some, of the vaccinated animals is encouraging-we know that many vaccines work because they prevent serious disease rather than preventing virus infection," Ball said. "However, the amount of virus genome detected in the noses of the vaccinated and unvaccinated monkeys was the same and this is concerning. If this represents infectious virus and a similar thing occurs in humans, then vaccinated people can still be infected, shed large amounts of virus which could potentially spread to others in the community."

Ball, who is currently involved in the development of a separate COVID-19 vaccine led by immunotherapy specialists Scancell Holdings and the University of Nottingham, said that the viral load detected in vaccinated monkeys warrants an "urgent re-appraisal" of the ongoing human trials of the Oxford vaccine.

"If the most vulnerable people aren't protected by the vaccine to the same degree, then this will put them at risk," Ball said.

In his article, Haseltine said that results from animal trials from the vaccine in development by Beijing-based Sinovac Biotech showed more promise than the Oxford vaccine.

The Jenner Institute responded to Haseltine's article on Tuesday, saying that direct comparison should not be drawn between the two animal trials.

"Whilst legitimate to try to ask questions about the relative efficacy of the two vaccines, drawing comparative conclusions about the studies is flawed given the differences in study design," the Jenner Institute said in a statement. "To draw definitive conclusions, one would have to compare the two vaccines side by side under the same experimental conditions."

The institute said that "in the end it is the impact on clinical disease that matters" and that ongoing clinical trials in humans will provide a better indication of the efficacy of the Oxford vaccine.