Sixty years on, doctor recalls difficult early TB fight

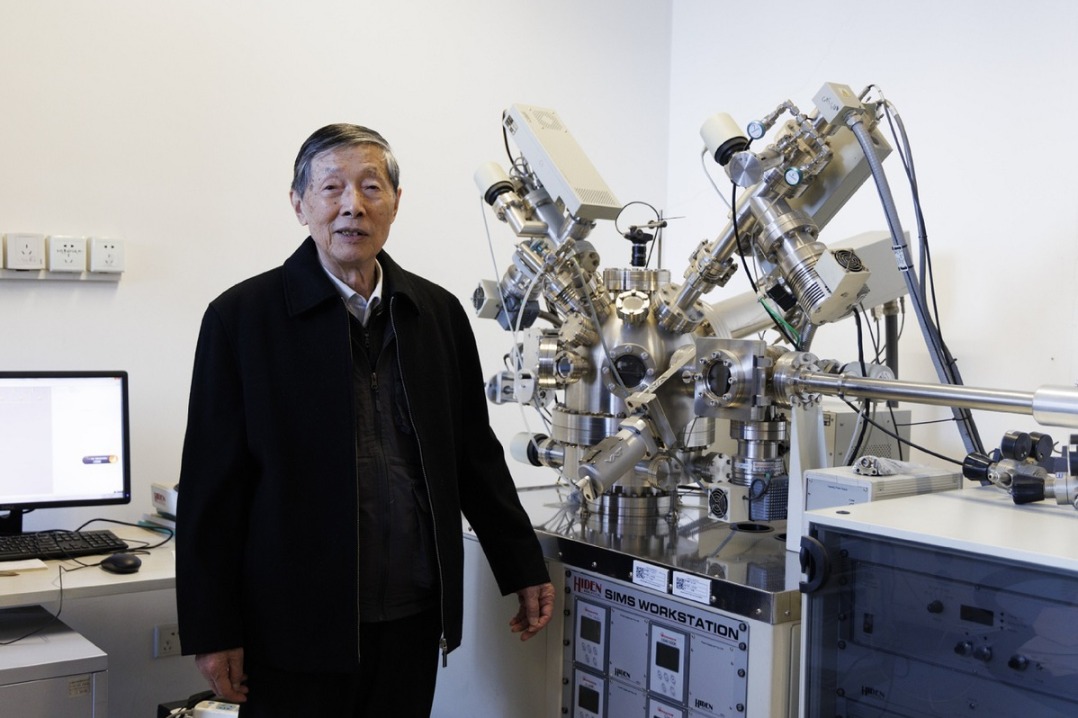

Every Thursday morning, a diminutive, silver-haired doctor walks into a diagnosis room at the Capital Medical University's Beijing Chest Hospital. Wearing spectacles, and carrying a magnifying glass and a pointer, she checks for signs of tuberculosis in the CT scans she examines.

Born in 1932, Ma Yu is the chief physician in the hospital's TB department. For more than six decades, she has been on the frontline of battling this contagious disease.

"Some people have said that I should enjoy retirement, but as a doctor, my responsibility is to make correct diagnoses and deliver effective treatments," she said. "I think I will retire naturally when my ability dwindles, and more young talent take my place. The fight against TB is sure to advance, and we are eventually bound to win."

TB is a potentially deadly bacterial infection that can easily be spread through a sneeze, a cough or close contact with contaminated objects.

Although the bacteria usually attacks the lungs, it can also infect other parts of the body, such as the kidney, spine and brain.

Before the 1950s, there were only 12 TB prevention and control institutions in China, with about 120 medical staff. The disease was widely known as the "white plague" because it rendered infected patients pale and weak.

In 1955, Ma graduated from Nanjing Medical University in Jiangsu province and was assigned to the Beijing Chest Hospital, then known as the Central TB Research Institute, and located on the outskirts of the city.

She said that at first, she overlooked the formidable nature of this enemy.

"I thought diagnosing TB was easily done by checking clinical symptoms, chest X-rays and sputum smears. Treatment plans also seemed clear and effective with the use of drugs like isoniazid, streptomycin-isoniazid, and streptomycin," she said. "But reality taught me a hard lesson."

According to the World Health Organization, China is one of the 30 highest-burden countries for TB.

Ma said that for patients, lung infections are usually just the beginning. Severe inflammation of the pleura (the thin layer of tissue that cushions the lungs against the chest cavity), peritonitis, meningitis caused by the bacteria, as well as lymph node TB and hematogenous TB(TB carried through the bloodstream) are among the toughest nuts to crack.

There is an old saying in China that out of 10 people with TB, nine will eventually die from the disease. "Seeing patients deteriorate is the most excruciating sight for a doctor," she said.

The scale of the threat did not demoralize Ma, who was bent on improving existing therapies and exploring new ones.

TB bacteria can destroy surrounding tissue and create cavities in the lungs. When infected patients cough, the bacteria accumulated in these holes is more likely to be expelled and be transmitted to other people.