Campus tale for ancient books

A hoard of pages

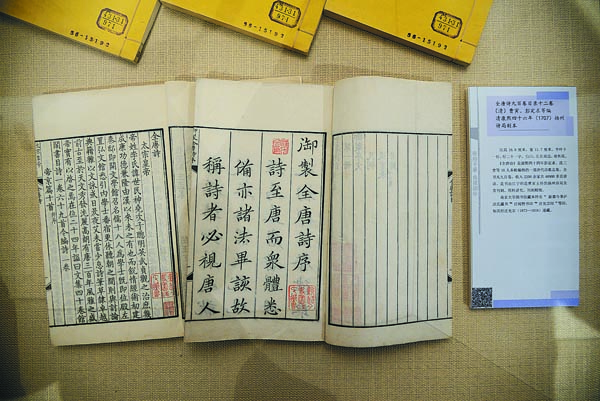

The national census of ancient books, which is almost finished, has registered more than 2.7 million ancient volumes. The total number of copies were estimated to be more than 30 million.

According to Zhang Zhiqing, deputy director of the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, about 20 percent of them are housed in universities, making them the second-largest collection category only after public libraries. In Peking University alone, for example, more than 1 million documents are housed.

In 2007, a national comprehensive project on conservation of ancient books was launched, which included the collections of the universities in the country's general blueprint for the first time.

Some major achievements have been made.

In Fudan University in Shanghai, for instance, a research academy focusing on the preservation of ancient Chinese books was established in 2015. This aims to help scholars not only of literature, history and ancient documentation, but also chemistry, biology and materials science, as well as other natural sciences. Many practitioners of intangible cultural heritage, like woodblock printing, are also hired by the academy to revive traditional craftsmanship.

"Unlike public libraries, where expertise is focused on humanities, universities have a wider range of expertise and will usher in new thinking with regard to the protection of ancient books," Zhang says.

Similar institutions were also set up in Sun Yat-sen University, in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, and Tianjin Normal University. In June, an academy specifically for preservation of ancient books of local non-Han ethnic groups was established in Guizhou Minzu University in Guiyang, Guizhou province.

Separately, in Nanjing, a national hub of the printing industry and bookstores during the Ming and Qing dynasties, another form of cooperation also demonstrates the city's extraordinary status in ancient cultural history. There is a cluster of custodians of ancient books, including the NJU, Nanjing Library, and various archives, as well as some vocational schools and an art academy in the city, which also train conservators of ancient books. Frequent communication among these institutions facilitates the study and preservation of the pages, as Shi points out.

Nevertheless, Zhang says the value of the huge collections of the universities can still be further demonstrated.

"A national-level alliance to specifically coordinate the study and preservation of ancient books in universities is still absent," Zhang says. "Most schools now rely on their own efforts."

Consequently, the first national conference of university libraries on ancient book protection was held at Nanjing University in 2019 to promote an exchange of experiences. The second edition of the conference was held at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou in July.

Another problem lingers: There is a lack of personnel in charge of the universities' collections of ancient books. For example, only two full-time restorers of ancient books work at Nanjing University Library.

Considering that about one quarter of the ancient books in the inventory awaits restoration, Shi says she needs more people for that position. However, for such a prestigious university, the academic requirement is demanding when introducing a new employee.

Training expertise through regular university syllabuses is one solution. In China, master's degrees related to ancient book restoration are bestowed in more than 10 universities, as Zhang points out. Nonetheless, no university has opened a department tailored to the field in undergraduate education.

"That means ancient books are not treated as an independent 'major' in college, and is only considered as a branch of fine art or publishing," Zhang says.

Based on successful trials of interdisciplinary research at Fudan University and other higher institutions, Zhang believes it is essential to set up a specific major focused on ancient books, thus forming a sustainable training system for the future.