Words for the song

A grand project to record a millennium of cultural achievements, initiated in the 10th century, still makes an impression today, Zhao Xu reports.

Family tree

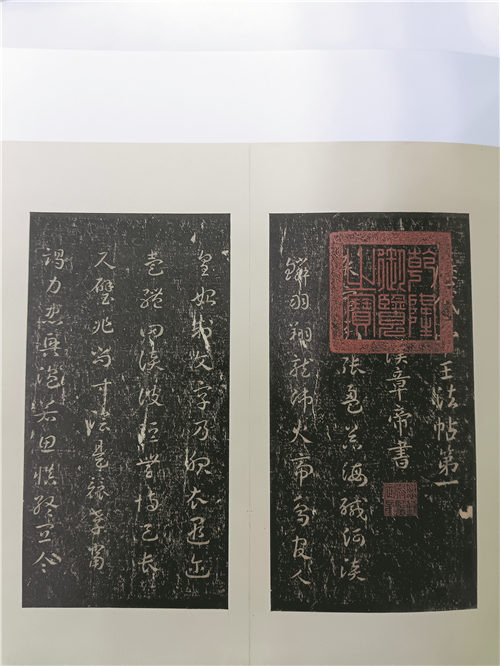

Repeatedly worn, the incised areas of the stone slabs gradually become less and less marked, resulting in rubbings with a decreased level of legibility. This is not to mention the occasional chipping of the stone, causing loss of characters here and there.

To solve the problems, recut stones were sometimes made. Yet by this point, decades or even centuries might have already passed. The original text probably had gone missing, and the "first stones" had fallen prey to the destructive forces of nature and men. Consequently, a new generation of engravers would have to rely on the rubbings that had come off the old stones, including later, considerably less complete copies. Thus, the need for clarification arose, and was often met by well-informed guesses.

It's fair to say that, if the rubbings of a renowned piece of calligraphy share a family tree, it's probably much more complicated than any a genealogist has ever studied. The many copies resulting from the "first stones" were disseminated over time and space, becoming the ancestors to all subsequent copies taken from a recut stone.

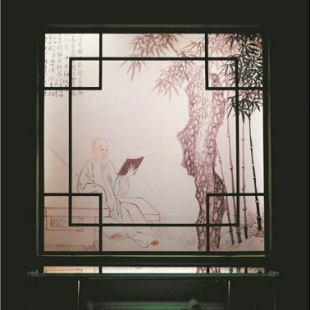

And during the entire Song Dynasty, numerous recut stones were made by private commission. Effectively encouraged by rulers like Zhao Guangyi, who by that time had changed his name to Zhao Jiong, and Zhao Ji — both hugely talented calligraphers in their own right, these learned men avidly made, collected and studied rubbings of calligraphy that had originated from the preceding eras, as well as their own times.

"Through their royal patronage of the art, the Song emperors were asserting for themselves a sense of entitlement to the country's splendid cultural and historical traditions, in which the rubbings were embedded," says Ho. "The necessity for making such assertions must be viewed within the context of what had happened in the previous half century."

In 907, the once-powerful empire of Tang came to its demise. Yet the Song empire didn't rise until 54 years later. Within those 54 years, China was ripped apart by competing military powers who were engaged in incessant warfare with one another for what turned out to be short-lived supremacy. Today, the period is known as "the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms", the term itself serving as a strong indicator of all the upheaval and division that had occurred.

"Under the Northern Song Dynasty, China became reunified. And anyone who was to enjoy an extended rule over this reunified country must legitimize himself on both political and cultural grounds," Ho says.

And such considerations, which were probably behind the compilation of both the 992 and 1109 editions of Model Calligraphy, had played out against a broader backdrop.

"The rise of calligraphy rubbing during the Northern Song time was paralleled by the invention of the movable-type printing technology. Closely related, both were products and propellants of a cultural resurgence, whose healing effect was felt when it was most needed," says Ho.