Slipping into history

Some of the ancient books were scattered or lost, some were different from the documents handed down through history. Notably, the folk documents have numerous, trivial remarks of grassroots life that were unseen in official history records, Wang says.

The 73-year-old historian is one of the guests of the show.

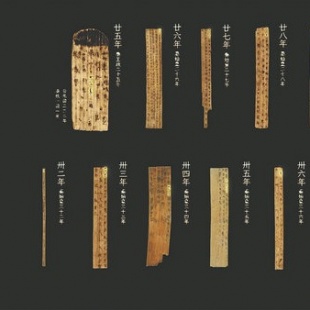

The first two episodes, featuring the Liye slips, pictured an ancient downtown with a prosperous marketplace. The region abounded with orange groves. Residents made wine from grains they grew. Local wax gourds and dried fish were presented to the emperor as tributes. Raw lacquer was used to decorate armor and shields.

Back then, people applied the multiplication table for calculation. They used simple fractions, too. The piece of slip inscribed with the table confirms that Chinese people started using the method more than 600 years earlier than the West.

Some of the slips listed the area of land reclaimed and the land rent, while some, functioning like today's passports, detailed personal information, especially descriptions on an individual's appearance.

The slips evidenced that the Qin Dynasty had developed an efficient postal system that facilitated its direct administration over localities. One such slip tracked the distance between different administrative units.

Archaeologists have also discovered what can be seen as the earliest envelope, marked with a postal priority.

According to Zhang and Wang, Qin officials needed to have written documents for every item of work — verbal requests didn't count — and each should be noted with the date and operators who handled the task, and how the work and goods were handed over.

"In fact, life of the Qin residents was not all that removed from us," Ma, the director, says.