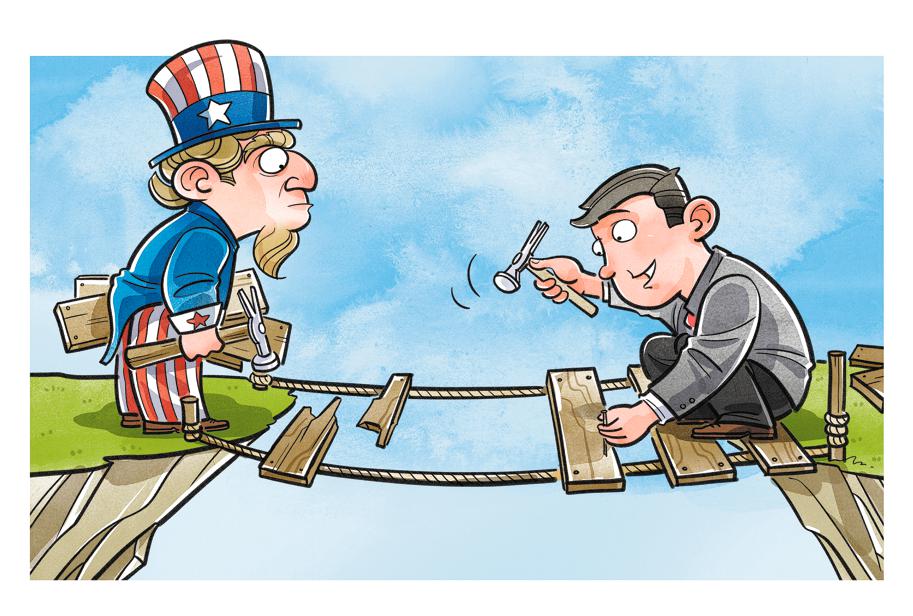

Focus on intermediate zones

The US is trying to gain the upper hand in its competition with China by pursuing zero-sum confrontation in the 'buffer zone regions'

As the US-China strategic competition has heated up in recent years, the United States has stepped up its criticism and attacks on the Belt and Road Initiative. It has even put forward some "alternatives" to the BRI in order to compete for influence in intermediate zone states.

Intermediate zone states serve as buffer zones between big powers and help avoid direct conflicts between them. They are also regions where major powers compete for influence and strategic advantages. The BRI improves economic connectivity on a transcontinental scale, enhances relations between China and other countries participating in the initiative, and strengthens political trust between China and intermediate zone states in a nonpredatory way, thus making important contributions to the reshaping of the global order driven by the collective rise of the Global South.

The US has also taken some steps to increase its political presence in the intermediate zone regions, but the alternatives it has offered have proved to be less attractive than the BRI, which has exacerbated the US' anxiety.

From the Barack Obama administration to the early period of Donald Trump's tenure, the US did not take an explicit stance against the BRI, and it even released positive signals occasionally. The US' strategy was to maintain policy flexibility. However, the success of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank was a turning point. After seeing the AIIB attract the participation of many nations, the US came to believe that China had the ambition to reshape the global financial governance structure.

The Trump administration's dramatic shift in its stance on the BRI was a prelude to the adjustment of its China strategy. It resorted to "minilateralism" to counter the BRI by rallying the support of a few key allies and pivoting to the "Indo-Pacific" region where there was still room to compete with China for influence. The Trump administration strengthened economic ties with some intermediate zone countries in Eurasia and Africa in order to gain bargaining chips for the US, preserve its core interests, and pressure these nations to reduce their cooperation with China.

The Joe Biden administration has resorted to new regional cooperation mechanisms to replace the BRI, instead of trying to strangle the BRI unilaterally.

First, the Biden administration has toned down the criticism of the BRI compared with the previous government, and has tried to denigrate the BRI from a third-party perspective in order to influence the perception of the BRI by intermediate zone states. In this way, it aims to peddle the US' alternatives to the BRI.

Second, the Biden administration has launched a set of "grand" infrastructure initiatives to counter the BRI, such as the Build Back Better World Initiative, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, and the "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity". It has also continued or transformed established frameworks such as the Quad security dialogue and the Blue Dot Network in order to create exclusive cliques in trade and investment, infrastructure building, and supply chain cooperation.

Third, the US seeks to hold its traditional allies, partners and neutral states together via hyping up the same political values shared by Western nations, so as to undermine the common identity of China and other Global South countries, and to exert its influence in intermediate zone states.

By launching a zero-sum confrontation in intermediate zone regions, the US is trying to gain the upper hand in its competition with China, which will have a negative impact on global security.

First, it will accelerate the collapse of the current global cooperation architecture.

The US' strategic competition targeting the BRI will make confrontation the mainstream of international relations, leading to overlapping of international institutions, resources waste and zero-sum competition. The US has abandoned the efforts to align with the BRI via multilateral cooperation frameworks and instead adopts a competitive strategy, which is more costly and risky.

Second, the US' competition strategy pursues its own narrow goals at the expense of global cooperation. In other words, by hyping up the "China threat", the US tries to win over the support of neutral states in its competition with China. As a byproduct of this strategic movement, the US' asymmetrical advantages over its allies have been strengthened, making it more difficult to restrain the US' unilateral global actions.

Third, the escalating China-US strategic competition has exacerbated the uncertainties in global economic cooperation. With the US mounting strategic pressure on China to pursue its unilateral interests, some intermediate zone countries have become more prudent in participating in BRI projects, resorting to a hedging strategy. The US' allies and partners that want to enhance cooperation with China are the countries that suffer the most.

The US presidential election has reached a critical stage. Despite the differences in their detailed policy visions, both the Democratic and the Republican parties seek to rope in third-party states to jump on the US' anti-China bandwagon, and prevent China from increasing its influence in the intermediate zone regions.

The BRI faces various challenges and opportunities. The US is a key external factor that influences the success of the BRI. It is imperative for China to grasp the essence of the challenges facing the BRI to promote the high-quality development of the initiative.

First, the China strategies of successive US administrations have shown a clear path of inheritance and evolution. The China-US competition over the BRI will be a major part in the broader strategic competition between the two powers for a long time to come.

Second, with the escalation of global infrastructure and institutional competition, China faces growing uncertainties in expanding cooperation with other developing countries under the framework of the BRI. This should prompt China to send clearer signals of its willingness to cooperate with intermediate zone states, thereby reducing the international community's misunderstanding and misrepresentation of China's global cooperation vision. It should make better use of its own comparative advantages to keep the BRI attractive to other nations.

Third, China and other major countries should manage their competition in the international system and seek mutual benefits, which is a new arena to ensure the stable development of major country relations. Based on the San Francisco Vision, China and the US should manage their differences in regional economic cooperation systems, promote mutually beneficial cooperation, and shoulder the responsibilities of major countries in order to benefit the whole world.

Ni Feng is director of the Institute of American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Zhu Chen'ge is an assistant researcher of the Institute of American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The authors contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.