Airstrikes add to Syria's economic woes

|

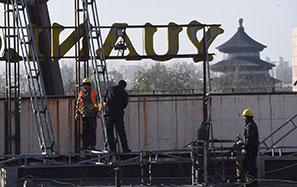

People shop in the ancient bazaar known as the Hamidiyeh Souk in Damascus on Monday. It is one of Syria's chief markets, once packed with tourists and visitors from around the country who shopped in the cavernous maze of arched alleyways.? Diaa Hadid / Associated Press |

The middle-aged salesman sat glumly among an array of shorts, khaki leisure suits bedecked with gold belts and dresses with plunging necklines in the ancient Damascus bazaar - luxuries few can afford in today's Syria.

He, like many traders, lost most of his customers when the country's civil conflict erupted in 2011, and his new clientele is far poorer: Syrians fleeing the fighting with barely any possessions.

Now, he fears there is even worse to come, as the US-led bombings of the Islamic State group target the country's modest oil reserves under the militants' control, sending oil and diesel prices soaring.

The effect is rippling through the economy, and traders fear they will not be able to absorb the increased costs, pushing them out of business and unraveling yet another key sector of Syrian society, already badly frayed by the conflict.

"We are hearing there's unimaginable prices for the winter," said the 50-year-old clothing vendor, whose first name is Amin, referring to the wholesalers he purchases from. "We have been through struggles before, but not like this."

Earlier this month, the government raised the subsidized price of diesel from 36 cents to 48 cents a liter just before a major Islamic holiday. The price of heating oil went from 73 cents a liter to 85 cents.

The increased prices were tied to the US bombing of small oil wells, tankers and pumping stations under the control of IS in the eastern Syrian provinces of Deir al-Zour and Hassakeh, which began in late September.

Syria has modest oil reserves. Before the conflict it was pumping 360,000 barrels a day; since the fighting it has only managed 16,000 barrels, said Syria economy expert Abdul-Qader Azouz.

The prices of other goods are likely to rise in the next few weeks, said traders at the Damascus bazaar, known as the Hamidiyeh Souk, an important measure of the economy's pulse.

One of Syria's chief markets, it was once packed with tourists and visitors from around the country who shopped in its cavernous maze of arched alleyways and ancient Roman columns, snapping up everything from antiques to wispy lingerie and sweets. Even amid the conflict, it is still an important shopping spot for the country's working classes.

Prices have already quadrupled over the past four years for most products in the market.

A printed leisure suit in Amin's stall cost $6 prewar; now it's $21. While that appears cheap by Western standards, salaries are low in Syria: Most civil servants and soldiers are paid around $100 a month.

Most of Syria's poor have already hit rock bottom. One 20-year-old vendor, Mohammed, who sells vegetables to try to pay his family's $90 monthly rent, said his family is relying on food aid donated by the social ministry.

"It's beans, sugar and oil," he said. "We are as you see us," he added, pointing to his shabby pants and jacket.

Umm Ahmad, 45, said her family is living off her son's salary as a soldier and her husband's pension.

"We have not bought diesel to heat our home for two years because it has become too expensive," she added. "We sit under blankets, we don't know luxuries anymore."

We have not bought diesel to heat our home for two years because it has become too expensive. We sit under blankets, we don't know luxuries anymore."