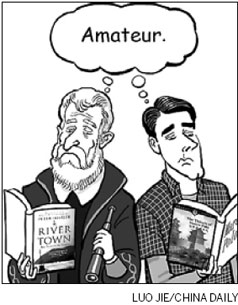

After writing about how Peter Hessler ruined my China life, I had the fortune to receive a message from Hessler, who was gracious enough to see the humor in my article (in yesterday's hotpot) and give sage advice to aspiring writers:

My sister sent me a link to your article about how I ruined your life. Sorry about that I definitely appreciated and enjoyed the humor. People aren't always so good-natured about it, that's for sure.

It's a funny phenomenon, and one that I remember when I first came to China. There were certain books that everybody read, and the longer you lived there, the more you might be inclined to resent them. It's a natural reaction in a place like China, where you're constantly learning and discovering. It's a very personal process, very intense, and a sense of ownership develops.

In River Town, I wrote about how I wasn't so charitable when I saw a couple of Europeans in Fuling (in Sichuan province), the first (and only) "uninvited" foreigners that I ever saw in town. I really did not want them there. I realized it was an unfair reaction, very childish; but I also saw that it was quite natural. After a long period of isolation I felt like it was my city.

During the years that I was in Fuling, Iron and Silk was the book that all foreign teachers read, and sometimes complained about. When I sent out the manuscript of River Town, a lot of reactions were clearly shaped by Mark Salzman's book. Most publishers rejected it, probably because there was already a successful book about teaching in China. Others wanted to build on it in narrow ways: One agent wanted me to cut it down into very short vignettes, like Salzman's book. I'm glad I resisted; over the years it's become clear that these are very different books and each has its own place.

When I met Mark Salzman at a literary event, and told him that the foreign teachers now complain about me as well. He laughed; he knew what I was talking about.

As time passes, it's more clear that China is such a big country that lots of different things can be written about it. This has always been true, but it wasn't so obvious back in 1999. When I sent out River Town, some publishers responded: "We don't think that anybody wants to read a book about China".

It's hard to imagine, but there wasn't this sense of China as such an important, varied, and energetic place. Nowadays there are many books coming out every year. It's more promising for a young writer.

China has been around for a long time, and experiences have overlapped for years and decades and even centuries. Recently I was reading Archibald Little's Through the Yangtse Gorges, in which he describes a Sichuanese banquet, and then he apologizes because it's hardly a new story: "Chinese dinners have been described over and over again, but I have narrated this one, as I think few have given an idea of their tediousness and the absence of all that we deem comfort."

Little wrote this in 1887! So I wasn't exactly breaking new ground with the baijiu banquets in River Town. Part of why China is such an interesting place for a young writer is that there's plenty of room to grow.

All the best,

Pete

China Daily

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|