A legend in his own lifetime

Updated: 2011-08-12 18:30

By Zhao Huanxin and Lu Hongyan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Chen Zhongshi is one of Xi'an's best-known attractions because of his hugely successful novel White Deer Plain, which describes life in the area before the founding of New China. Zhao Huanxin and Lu Hongyan report.

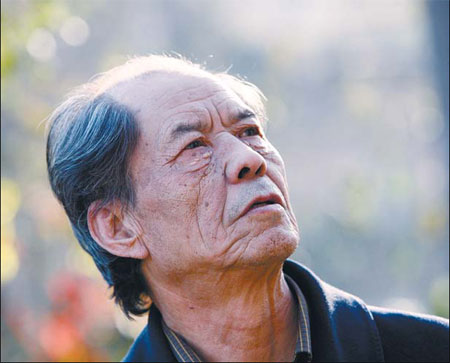

The Terracotta Warriors in Xi'an are obviously a must-see, but so is "old farmer" Chen Zhongshi.

Wrinkle-faced and gravel-voiced, the 69-year-old looks more like a farmer than an author who has created a literary storm.

White Deer Plain, his magnum opus, has sold more than 2 million copies since it won China's top literature award in 1998.

The book of half a million characters tells of the struggles of two rural families, fights between arch foes, love affairs and spiritual life on the plain to the east of Xi'an, half a century before the founding of New China in 1949.

The novel has been hailed by critics as a modern classic and is still selling strongly.

"It is encouraging to see that nearly two decades after its debut (in 1993), readers are not tired of it," Chen says.

Neither are they tired of the author himself. Today, Chen is one of the most sought-after personalities in the ancient capital of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

These book fans, travelers and researchers believe the best way to understand a man of letters is not just to read his book but to meet the author in person.

Here is a man with a tough appearance but a tender heart, sensitive to his surroundings and everything happening on White Deer Plain.

He says that when he writes, however, he must not be disturbed.

"However wretched the room, I don't care, but it must be a place where I can be alone," he says. "The presence of anyone else would scare away my characters - they would not dare come forth, and I couldn't write a solitary word."

This explains why Chen in 1988, when he was 46, spent four years in his ancestral house drafting his novel, preferring its seclusion to busy Xi'an.

The house of his ancestors proved to be a source of inspiration.

There, Chen interviewed locals to learn more about White Deer Plain and unravel the mysteries of his family.

One villager told Chen that he had met Chen's great-grandfather.

"He was a tall man, always standing straight, with a commanding authority in the village," the villager says. "When he walked through the village, women breast-feeding with their blouses open would return home and dare not come out until he was far away."

This description became part of the portrait of Chen's patriarch of the imaginary village on White Deer Plain - Bai Jiaxuan, the protagonist of Chen's book.

"The key to writing, whether the writer has a spring mattress or just an adobe bed to sleep on, whether he has a painting or just a hoe to hang on his wall - the key is how sensitive his nerves are to words," Chen says.

He says one of the people who lived in his village 200 years ago was a man called Li Shisan, an outstanding and successful playwright.

Li enjoyed writing so much he often forgot to eat when he worked, but was so poor that at the age of 62 he had to mill his own wheat.

Li died tragically after fleeing his house when the emperor alleged his plays spread "obscenities".

Chen's Li Shishan Works on a Mill is a popular work that has appeared in many literary collections.

While preparing to write White Deer Plain, Chen went to Lantian county, about 20 km from Xi'an, and browsed the county annals. Nearly a quarter of the county's historical records were devoted to chaste women who remained "loyal" to their deceased husbands by never remarrying.

"My heart trembled. So many young and vivacious lives were ruined by the lifeless statutes imposed on them, and after all the cruel years, they died, only to be awarded a plaque and a few centimeters of words in the annals, to commend their chastity."

So, he came up with a protagonist in his novel, the sensual Tian Xiao'e, who defies all the feudal codes, lives according to her instincts and has relationships with several men.

As a child, Chen saw men in his village punish a newlywed woman who fled from the family she had married into.

She was tied to a tree and the men used thorn sticks to beat her, one after another. Her cries have haunted him for years, he says.

White Deer Plain also contains many smutty jokes that Chen had picked up over the years, used to illustrate the streak of wildness in Tian, who was beaten in the same way after she was found to be an adulteress.

Chen says he spent several days accompanying his father when he was dying from cancer. He was tight-lipped throughout the ordeal, but just two days before he died, the old man finally said: "I'm sorry to you for one thing. I shouldn't have asked you to drop out of school for that one year."

Unable to support two sons through junior high school, he had removed Chen from school so his older brother could go to teachers' college and support the family. It cost Chen the chance of going to college.

"I had forgotten this after so many years, but my father still had it on his mind up to his death," Chen says. "What a burden he had carried."

Chen taught himself history and literature. He honed his writing skills and completed nine highly acclaimed novellas before turning out his masterpiece, White Deer Plain.

Production of a movie of the same title has just finished, Chen says, adding that he is not sure when it will be released as it is in postproduction.