Developed nations should stop devaluing currencies

The world breathed a collective sigh of relieve when finance ministers of the leading economies declared earlier this month in Moscow that they would refrain from waging a currency war.

In a communiqu, they said: "We will refrain from competitive devaluation. We will not target our exchange rates for competitive purposes."

They also refrained from naming Japan as the culprit for instigating the latest threat of global economic warfare. It has adopted aggressive monetary and fiscal policies that have driven down the value of the yen by 20 percent against the US dollar in the past couple of months. Instead, the communiqu sought to reaffirm the G20's commitment to move "more rapidly toward more market-determined exchange rate systems and exchange rate flexibility to reflect underlying fundamentals".

Of course, we should refrain from finger-pointing without clear and indisputable evidence of currency manipulation.

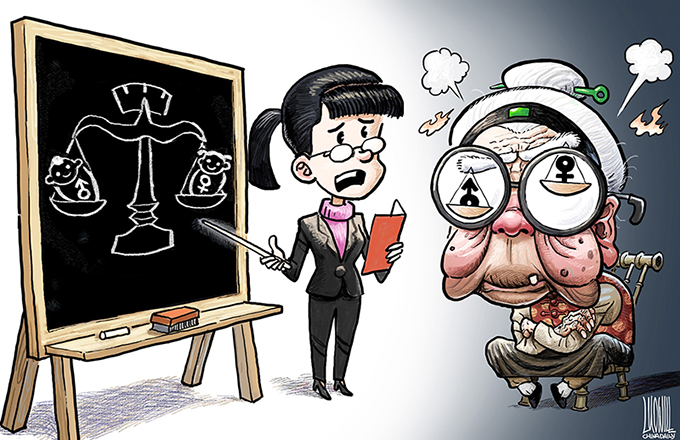

But for years, the United States has been leading a campaign accusing China of deliberately keeping down the value of the renminbi to boost its exports. US economist Paul Krugman wrote numerous times about what he considered to be China's flagrant currency manipulation. Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney vowed to declare China a currency manipulator on his first day in office. His campaign made it abundantly clear this was one of the very few issues on which the conservatives and liberals in the United States agreed.

In fact, the renminbi has appreciated a total of nearly 32 percent since 2005 when exchange rate reform was introduced.

While denouncing China for alleged currency deception, many US economists and politicians also noted that the low value of renminbi, which they considered artificial, had caused inflation and driven up costs, negating whatever gains in competitiveness a low currency bestowed.

As such, there is little to gain by China, or any other developing country, from currency manipulation, especially those countries that are heavily dependent on imports of oil and other raw materials. Unlike the US, which has been a major benefactor of the latest depreciation of its currency, especially when inflation was kept in check at just above 2 percent in 2012 by weak domestic demand. The weak dollar has helped its exports.

What's more, the dollar, despite its weakness, has regained its supremacy as the world's reserve currency, as the status of the euro has been badly battered by the sovereign debt crisis. This has allowed the US to continue to borrow at negative real interest rates while servicing its debt with the weakened dollar.