Niceties of old-style diplomacy still work

|

|

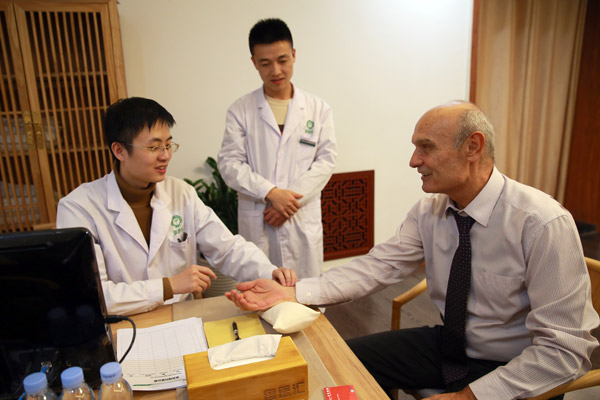

Milan Bacevic, Serbian ambassador to China, experiences TCM diagnosis at "TCM Health Day For Ambassadors" in Beijing, Dec 12, 2016. [Zou Hong/China Daily] |

His definition of the diplomat's role encapsulates its essential requirements-sycophancy and duplicity.

These days, world leaders can communicate instantly with both their constituents and each other with no more effort-and frequently no more thought-than it takes to type 140 characters on their Twitter feed.

US President Donald Trump is a master of the new art and appears to follow a rule adopted from his business career that, even in diplomacy, you should aim to cut out the middleman. But the problem with instant messaging is that it offers speed at the cost of reflection, and brevity at the cost of precision. It also dispenses with that essential diplomatic tool-procrastination.

The diplomat of a previous era, called on to defuse some looming crisis engendered by an intemperate remark or gesture from one of his or her political masters, would invariably assure the host government that the embassy was "urgently seeking clarification". (Translation: "We're going to delay and obfuscate until you've forgotten all about it.")

These days, by contrast, social media gives political leaders a virtual "hot line" to abuse each other directly and very publicly without recourse to diplomatic intermediaries. Many may welcome the more direct approach spearheaded by Trump as a breath of fresh air. Like a man who has fired the White House chauffeur and grabbed the steering wheel himself, Trump careers along the information superhighway, shoving aside enemies both foreign and domestic. It must be invigorating, as long as you don't crash.

You might also argue that the direct approach to diplomacy is more honest.

In the past, the blazing confrontation between the United States and Germany over the future of the Western alliance would have been described in diplomat-speak as "full and frank exchanges". With social media at his disposal, Trump can cut through the hypocrisy by tweeting: "We have a massive trade deficit with Germany, plus they pay far less than they should on NATO & military. Very bad for US. This will change".

But despite the superficial attractions of this "tell it like it is" approach, there is still much to be said for old-style diplomacy. The niceties of diplomatic protocol can help to defuse tensions, rather than enflame them.

In its guide Protocol for the Modern Diplomat, the US State Department cautions new recruits that the informal US approach does not always go down well with other cultures. According to the guide: "Tremendous differences exist in how close people stand to socialize, how loudly they speak, and how much eye contact they maintain." And, it might have added, don't push fellow heads of state aside to get to the front of the line.

For all the stuffiness and insincerity of the diplomatic circuit, traditional diplomats probably do continue to play an essential role, even in an era of instant communications and presidential tweeting.

Diplomats alone cannot prevent conflicts, as history shows. But a temperate diplomatic approach can help calm the waters. "A soft answer turns away wrath; but grievous words stir up anger", as it says in the Christian Bible.

The essence of the profession is not, of course, to be gratuitously generous to the other side, but rather to gain advantage for one's own, if necessary by lying for one's country.

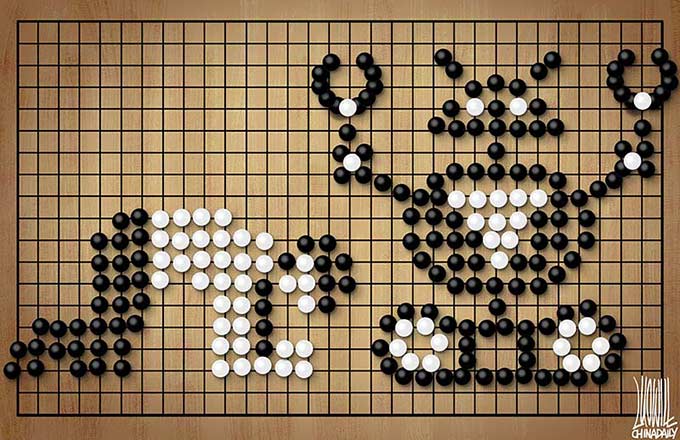

In the words of the great Chinese strategist Sun Tzu: "The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting."

The author is a senior media consultant for China Daily, Europe.

editor@mail.chinadailyuk.com