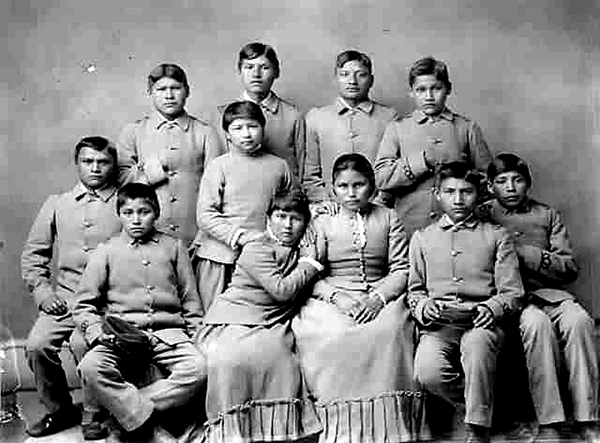

Stolen identity

Tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans were sent to boarding schools in an assimilation program one bureaucrat saw as part of 'a final solution of our Indian Problem', Zhao Xu in New York reports.

Although the number of federally run assimilation-era Native American boarding schools is put at 26, the government also ran many on-reservation boarding schools and provided funding to private boarding schools run by religious denominations. The Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, has identified about 370 of them.

Between the 1880s and 1930s, through its non-Indian agents, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs trawled the reservations for students to fill the schools. The bureau, which was also responsible for distributing food, land and executing other provisions in treaties with Native American tribes, routinely withheld provisions from those who refused to send their children to the schools. In some cases its agents-who had a quota to fill-simply kidnapped children. It has been estimated that by 1926 nearly 83 percent of Native American school-age children were in the system.

Before the Carlisle school closed in 1918, more than 10,000 Native American children from 140 tribes had been through it. Many, including Sophia Tetoff, never got out alive. Native Alaskan children became targets for the country's assimilation campaign after the US bought the territory from Russia in 1867.

Deb Haaland, the US Secretary of the Interior and the country's first Native American cabinet secretary, said the discoveries of unmarked graves in Canada had left her "sick to my stomach". Haaland, whose great-grandfather was a survivor of the Carlisle school, launched the Indian Boarding School Initiative in late June.

The stated goal of the initiative is to identify boarding schools, their students and any possible cemetery or burial ground connected with them, what Torres calls "the tangible side of things".

It is the intangible that has proved to be the most "deleterious", with cycles of nefarious influences "rippling out" across generations, says Eric Anderson, professor of American Indian studies at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas. Anderson, whose mother was Native American, has taught at the university for 13 years. It opened in 1884 as an off-reservation Native American boarding school, before becoming, in the post-assimilation years, a high school, a community college and ultimately a university exclusively for Native American students.

"All my students are connected, at least tangentially, to the boarding school experience through their ancestors, and very few of them speak their own indigenous languages," Anderson says. "In some cases they came from tribes where there are virtually none, none at all, of fluent speakers. The boarding schools had essentially beaten the language out of multiple generations."

He was referring to the punishment students were often subjected to for talking in their native tongue, even among themselves. This included having their mouth washed out with soap, being held in dark solitary confinement for days, or forced to run a gauntlet whereby the victim went down in between two lines of fellow students, who swung their belts at the victim, egged on by the teacher. All present were in no doubt of their fate if they broke the same rule.

As their language died, so did their songs, music and rituals, "things that contain not just an epistemological outlook but also stories, histories, moral codes and values", Anderson says.