Stolen identity

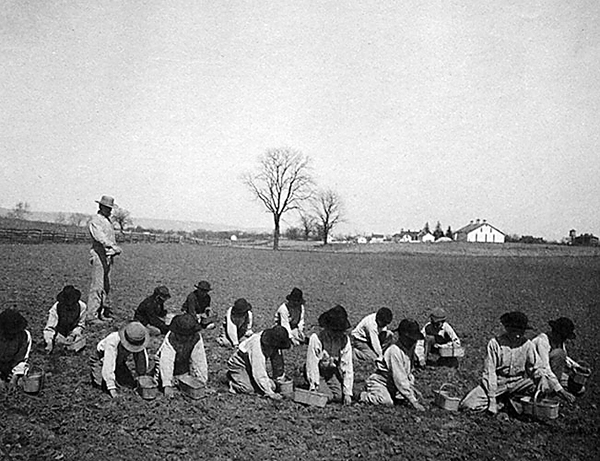

Tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans were sent to boarding schools in an assimilation program one bureaucrat saw as part of 'a final solution of our Indian Problem', Zhao Xu in New York reports.

In fact on the very first day at the school they were stripped of all "outward Indianness". Their long hair, a source of pride for all American Indians, was viewed as a sign of savagery and instantly sheared-boys' mowed to military style and girls' reduced to short bob.

Their embroidered and fringed leather outfits and moccasin boots, sewn by mothers and grandmothers, were removed and replaced in many cases by military-type uniforms. In fact many boarding schools, including Carlisle, were built on old army barracks, some used in wars against the Indians. In some cases shoes provided were so small that the wearers were left with deformed feet.

The children, who at this point could barely speak a word of English, were given English names, before being baptized and told that "God was a starving white man, with long hair and blue eyes and a beard", says John Smelcer, an American author who writes about the boarding school experiences in both poetry and historical novels.

For Lindsay Montgomery, author of the book Objects of Survivance: A Material History of the American Indian School Experience, two things she has studied speak powerfully about this experience. One is a medicine pouch beaded with the image of a Christian church, made by a boarding school student employing indigenous handicraft; the other is a set of leather dolls students made that wear traditional Indian dresses, which "would have helped children imagine themselves".

"There we can see some space, however tiny it was, where Native kids could express their own traditions in which they took pride," says Montgomery, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona.

But such space was not always available. During Montgomery's research for the book she came across the story of an Indian girl named Clara who attended Tulalip Boarding School in Washington State. Caught teaching her fellow students how to weave traditional Indian baskets, she was hit repeatedly on the knuckles with a metal-edged wooden ruler until her fingers started to bleed.

Both the medicine pouch and the dolls came from the collection of one man, Jesse H. Bratley who, around the turn of the 20th century, worked in Native American schools across five reservations in the American West. He believed that by bringing indigenous children into English-speaking Western society he was doing them good, even as he became enamored of their culture, collecting ceramics, dresses and shields now held by the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. This was typical of Bratley's era, Montgomery says.

"In his autobiography, Bratley talked about how Native culture was fast disappearing and how he needed to go out and document it, which he did through his collections and photographs. But there's a disassociation between the living culture and the exotic one he sought to preserve and which he preferred to view in a museum."

Montgomery pointed to the "fantasizing" of American Indian culture that continues in the US to this day, fueled by popular media and institutional racism.

In 1904 Bratley attended the World Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, where a replica boarding school was an exhibit. But there was no sign of the pervasive physical, mental and sexual abuse, overcrowding and poor sanitation that inevitably had any infectious disease running rampant, and ultimately the many deaths, the vast majority of which remain undocumented.