|

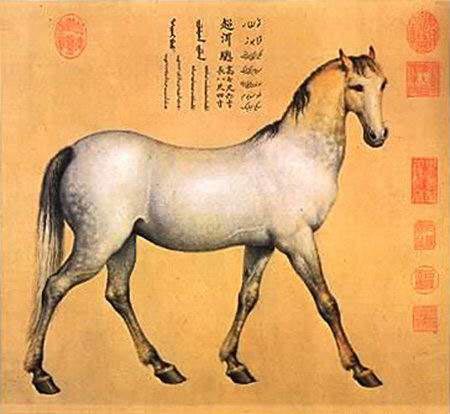

| This painting, one of Giuseppe Castiglione's Afghan Four Steeds, features a horse named Chaoni'er. Castiglione was an Italian missionary. |

|

The era when people depended on steeds for transportation or warfare has long gone, but the zodiac animal has left numerous genetic footprints on spoken Chinese, writes Raymond Zhou. Yao Shaoshuang has been the most photographed horse rider in China in the past month. Donning a cowboy hat and boots for three days, he rode a black horse from his workplace in Pixian to the city of Dujiangyan, where his mother-in-law lives, after failing to secure a bus ticket for Spring Festival travel. (The county and city lie to the northwest of Chengdu, the provincial capital.) His image appeared all over the Internet, and Yao said he received hundreds of calls, including interview requests, from the media. Apart from his inability to obtain a ticket, Yao said he made his trip on horseback as he was eager to reach his destination and to impress his in-laws on his first visit to his wife's family. In Chinese, there is a common word, mashang, literally "on horseback" and means "right away" or "fast". It was clearly not coined after modern modes of transportation were invented. But the irony in 24-year-old Yao's case is that he covered the 70 km in three days, slower than most hikers. The truth, when it emerged, proved to be an anti-climax. Yao works for an equestrian club and the horse he was riding was a Dutch Warmblood (a horse of medium build designed for sports) from the Netherlands worth half a million yuan ($82,000). Normally, such an expensive import would not appear on a hard, asphalt road, but this may also explain the ultra-slow speed, complete with numerous photo opportunities. Moreover, the journey was a publicity stunt, not for himself but for a business. Yao, a local equestrian sports champion, kept quiet. However, other clubs said they had received requests from advertisers who wanted to get in on the horseback bandwagon, but owners could not bear to see their costly investments stray far from soft grass and well-maintained stables. Some even viewed Yao's actions as animal abuse. Good humor The fad for placing objects on horseback in the hope of fulfilling financial dreams started rather innocuously and in good humor, but quickly transformed into materialistic vulgarity. Blessings and good wishes were quickly replaced by hard cash, such as placing a wad of banknotes on horseback. Since real horses proved hard to come by, enlarged toy horses were used. People even piled miniature houses on the horses in a desperate bid for the financial wherewithal to purchase apartments. One man, with a touch of ingenuity, reportedly placed a pair of toy elephants on top of a toy horse, because the Chinese word for "date" has "xiang" in it, which can be stretched to encompass the elephant. If you let a smaller horse piggyback on a larger one, it could mean that the object of your desire is a BMW, as the German car has a vague Chinese transliteration as "precious horse". Word games involving the horse appear frivolous, but often have cultural and historical connotations. Chinese like to describe being victimized by foreign invasion as being trodden under iron hooves. In Chinese history, the economically developed and culturally sophisticated Han majority on the central plains were repeatedly attacked and pillaged by northern tribes. Part of the reason, many scholars believe, was the mode of travel used by the nomads. While they swooped down in an iron-hoofed stampede, the Han could only flee on foot. Hence, the vivid depiction of being trampled. Celebrated stallions The Han were not as expert at horse riding as the northern tribes, but horses were not uncommon. It was rare, though, for them to be venerated like the Six Steeds of the Zhaoling Mausoleum in Shaanxi province. These warhorses belonged to Emperor Taizong (AD 598-649), also known as Li Shimin, of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). He commissioned artisan Yan Lide and painter Yan Liben, who were brothers, to carve six warhorses he rode before he built his empire. The reliefs, each standing 1.7 meters high and 2 meters wide, used to flank the sacrificial altar to the north of the mausoleum. The steeds have poetic names that mostly denote their markings. Four of them were hit by arrows and the emperor left memorial tributes to each of them along with records of the military campaigns in which they carried him or in which they fell. The carvings were broken apart early in the 20th century and two of them were smuggled out of China. They are now housed in a museum at the University of Pennsylvania, while those remaining in China are in a museum in Xi'an, the Shaanxi provincial capital. By aesthetic standards of the day, they were quite realistic. Horses made frequent appearances in ancient scroll paintings, but most were static and inconspicuous, acting as loyal companions to reclusive scholars or officials seeking sanctuary in nature. Unlike ancient artists obsessed with saddled horses, Xu Beihong (1895-1953) preferred feral and wild ones. Trained in France, the Chinese master studied equine anatomy, spending hours observing horses' movements and expressions. Especially fond of Mongolian breeds, he left a treasure trove of up to 1,000 sketches. Xu's portrayals of horses galloping or trotting past, in a rich variety of poses, are some of the most captivating of their kind. Using mostly black ink, they combine the best methods from East and West. The lines and brush strokes are simple, yet invariably evoke the essence of the animals. They are a contrast to the horses painted by Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766), an Italian missionary who created many eight-horse images for the Qing emperors. In full color and resembling traditional European oil paintings, they were, however, closer in spirit to the Chinese style of depicting horses. There was nothing of the energy and exhilaration found in Xu's drawings. Different emphasis While the tale of Pegasus is not widely known in China, "flying horse" is by no means a strange term. Several brands are named after it, most notably a cigarette with a long history. It is true that China may pale in comparison with the West in creating talking horses or weeping horses in art and literature, with most of our horse-related prominence being in our vocabulary. But before we get to that, I'll point to the different emphasis, or rather East-West focus, on different aspects of the horse. For example, most English words for "horse" define the animal by age and gender, such as colt for a male horse under the age of 4, filly for a female horse less than 4 years old, mare for a female aged 4 or older, yearling for one between 1 and 2 years old, and foal for one younger than a year old. Gelding and stallion denote castration or non-castration. In contrast, most Chinese descriptions for the horse concern colors. Biao (驃) is yellow; liu (騮) is red with black mane and tail; yan (骃) is grayish; li (驪) is black; guo (騧) is yellow with black mouth; qi (騏) is purplish black; hua (驊) is red like the fruit date; xing (骍) is another kind of red; cong (驄) is blue; zhui (騅) is black with white feet; and mang (駹) is black with white face. Ju (駒) and ji (驥) refer to young and old horses, but not how young or how old, while jun (駿) and nu (駑) are names for fast and slow ones. We have more names for different horses than there are zodiac animals, but most of them appear to have been inspired by the color spectrum. We Chinese also have an equivalent for the term "prince charming" that has a whiff of the fairytale about it. It is "prince on a white horse" or "white-horse prince". But a study of the colors of horses' coats made me realize the inherent irony in this Disney-like phrase: With rare exceptions, a horse turns gray or white as it ages, and is usually born with a darker shade. If you are not sure, check the skin underneath a white horse's coat. So, associating a prince with mortality is not really the best way to present his youthful charm. However, since most of us are not equine veterinarians, we can be excused for envisioning this most desirable companion for females in the color of purity and forget about old age. Linguistic record The Chinese attitude toward the zodiac animal of 2014 is embedded in a profusion of expressions handed down and enriched through centuries of man-horse dynamics. Apart from serving as a symbol of loyalty and bravery for military heroes, the horse is often praised for its endurance, as illustrated in the proverbial thousand-mile horse. Perhaps the best analogy for man's relationship with the horse concerns Bole, a wise man with an eye for the next thousand-mile horse. Here, the human being is the talent scout, manipulator and trainer, while the horse is to be observed for potential, and groomed. A mentor-protege parallel is quite obvious. As such, the horse may also become the recipient of tiger-mom-style Chinese tough love, as in the phrase "A horse has to be whipped to run." But ancient Chinese tended to identify with the animal so closely that when they talked about their horses they could be talking about themselves. "To err is human" has a Chinese equivalent: "Man may make mistakes and a horse may miss a step". Chinese in general have a weakness for patting a horse on the butt, a friendly gesture that has since evolved to mean sycophancy. When you miss a beat and end up patting it on the leg, you have failed in the unctuous act of flattering someone. In these sayings, the horse is no longer man's servant or apprentice, but an object of appreciation and power. This kind of duality is also present in the traditional Chinese perspective on entertainers. While the man-horse power dependence may change with different situations, the horse reigns supreme in the equine hierarchy. The donkey and the mule usually appear as sidekicks or foils in Chinese folktales to make the horse appear as magnificent as the superhero in a Hollywood fantasy film. About the only time the horse is overshadowed is by the appearance of the camel, which is so much bigger that, according to Chinese lore, even the thinnest one is still larger than the horse. But then, the camel has never been credited as a conqueror of the world. There is no doubt that Chinese, ancient or modern, love the horse. But those who take "ma" (horse) as their surname cannot prove they are any different from the rest of us. As it happens, Chinese Muslims took the sound for Muhammad and sinicized it to ma, hence the largest family name in this ethnic group. Also, Chinese rarely use the word in any last name for its literal meaning, otherwise wang (or wong in Cantonese, meaning king) would be the most coveted of all. But even a king or emperor could enhance his regal stature while posing on a horse. |

雖然馬匹用于交通和戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)的年代一去不復(fù)返了,但是,與十二生肖中的“馬”相關(guān)的語(yǔ)句在中國(guó)語(yǔ)言中留下了印跡。 過(guò)去的一個(gè)月中,“馬上哥”姚少雙的照片頻繁出現(xiàn)在各大媒體上。春運(yùn)買(mǎi)不到車(chē)票后,姚少雙戴上牛仔帽、蹬上靴子,騎著一匹黑馬從工作地郫縣到都江堰市去拜見(jiàn)岳母。這趟行程歷時(shí)3天。(郫縣和都江堰市在四川省會(huì)成都的西北部。)姚少雙在網(wǎng)絡(luò)上火了,他說(shuō)自己收到了近千個(gè)電話,媒體的電話采訪也包含在內(nèi)。姚少雙說(shuō),除了買(mǎi)不到車(chē)票這個(gè)原因外,自己騎馬還因?yàn)橄胍琰c(diǎn)到目的地,第一次拜訪岳母,要留個(gè)好印象。 漢語(yǔ)中有一個(gè)常見(jiàn)詞語(yǔ)叫“馬上”,字面意思是“在馬背上”,也有“立刻”和“很快”的意思。這個(gè)詞語(yǔ)當(dāng)然不是依據(jù)現(xiàn)代的交通運(yùn)輸方式衍生出來(lái)的。但是,這個(gè)詞語(yǔ)對(duì)于24歲的姚少雙而言,頗具諷刺意味了。姚少雙用了3天時(shí)間走了70千米的路程,這比徒步走還慢。 當(dāng)真相浮出水面的時(shí)候,令人大跌眼鏡。姚少雙為一個(gè)馬術(shù)俱樂(lè)部效力,他騎的馬是荷蘭溫血馬(一種體型中等的體育競(jìng)技馬)價(jià)值50萬(wàn)元。 一般來(lái)講,這么貴的進(jìn)口馬不會(huì)出現(xiàn)在硬硬的柏油馬路上。但是,這也解釋了為啥這匹馬走路速度奇慢,給別人提供了那么多的拍照機(jī)會(huì)。 此外,這次騎馬行為純屬作秀,姚少雙不是要自己出風(fēng)頭,而是為了商業(yè)炒作。 對(duì)于這些,姚少雙這位當(dāng)?shù)氐鸟R術(shù)冠軍不予回應(yīng)。然而,其他的馬術(shù)俱樂(lè)部也收到了廣告商的邀約。廣告商們想要用“馬上”這個(gè)詞做噱頭。但是,馬術(shù)俱樂(lè)部拒絕了,因?yàn)樗麄儾辉敢饪吹竭@么昂貴的馬離開(kāi)軟軟的草地和維護(hù)良好的馬廄,走在硬梆梆的柏油路上。有些人看了有關(guān)姚少雙的報(bào)道后,認(rèn)為他是在虐待動(dòng)物。 幽默 人們把東西放在馬背上,表示對(duì)實(shí)現(xiàn)經(jīng)濟(jì)夢(mèng)想的希望。這種風(fēng)尚在最初流行的時(shí)候是一種幽默表現(xiàn)形式,沒(méi)有什么不好的。但是,這件事很快就變得粗俗起來(lái)了。 美好的祝愿很快被物質(zhì)欲望所取代。比如,有人把一團(tuán)偽鈔放在馬背上,表示馬上有錢(qián)。因?yàn)檎鎸?shí)的馬匹很少見(jiàn),人們用填充的玩具馬代替真實(shí)的馬。有人甚至把微型的房子堆在馬背上,迫切希望能夠經(jīng)濟(jì)寬裕、馬上買(mǎi)房。 據(jù)說(shuō),有人很有創(chuàng)意地把一對(duì)玩具大象放在了玩具馬的背上。因?yàn)樵跐h語(yǔ)中,“對(duì)象”一詞有“象”字在里面。這樣以來(lái),往馬背上放的東西的范圍延伸到了大象。 如果你把一個(gè)小的馬寶寶放在一匹大馬上,這意味者你想要擁有一輛寶馬汽車(chē)。因?yàn)椋聡?guó)出產(chǎn)的汽車(chē)BMW在中文中的音譯是“寶馬”。 關(guān)于馬的文字游戲看起來(lái)很沒(méi)意思,但是它一般有文化、歷史內(nèi)涵。中國(guó)人在描述遭到外國(guó)侵略時(shí),喜歡用到“鐵蹄之下”這個(gè)短語(yǔ)。 在中國(guó)歷史上,經(jīng)濟(jì)文化先進(jìn)的漢族人口占大多數(shù),居住在中原地區(qū)。他們經(jīng)常遭到北方游牧民族的劫掠。 學(xué)者們認(rèn)為,漢族受游牧民族侵?jǐn)_的部分原因在于游牧民族的活動(dòng)方式。當(dāng)游牧民族騎著鐵蹄馬南襲的時(shí)候,漢族人只能徒步逃跑。因此,“鐵蹄之下”很生動(dòng)地描繪了游牧民族對(duì)漢族的蹂躪。 名馬 漢族不如北方游牧民族那樣善長(zhǎng)騎馬,但是,他們的馬卻非同尋常。馬很少像陜西省的昭陵六駿那樣受到人們的推崇。 這六匹戰(zhàn)馬是唐朝(公元618-907)皇帝唐太宗(公元598-649)李世民的坐騎。他命令工藝家閻立德和畫(huà)家閻立本兄弟二人雕刻出他建唐朝前騎過(guò)的六匹戰(zhàn)馬。昭陵六駿位于昭陵北面的祭壇兩側(cè),每塊石刻高約1.7米,寬約2米。 戰(zhàn)馬的名字很有詩(shī)意,大部分馬是根據(jù)馬身上的斑紋命名的。有四匹馬在戰(zhàn)爭(zhēng)中中箭。為了紀(jì)念戰(zhàn)馬,李世民給每匹馬寫(xiě)了墓志銘,上面記載著哪場(chǎng)戰(zhàn)役用的哪匹馬、在哪場(chǎng)戰(zhàn)役馬死了。 在20世紀(jì)早期,昭陵六駿的雕刻被分割開(kāi)來(lái),有兩個(gè)走私到了國(guó)外,現(xiàn)收藏在美國(guó)賓夕法尼亞大學(xué)博物館。剩下的保存在陜西省省會(huì)西安的博物館。 從當(dāng)今的審美水平來(lái)看,馬的形象很逼真。馬的形象經(jīng)常出現(xiàn)在古代的卷軸畫(huà)上。但是,許多馬都是靜態(tài)的,與畫(huà)面不協(xié)調(diào):它們或是忠實(shí)地陪伴著隱居的學(xué)者,或是忠實(shí)地守候著隱居田園的官員。 古代的藝術(shù)家熱衷于畫(huà)被馴服的馬,畫(huà)家徐悲鴻(1895-1953)卻對(duì)畫(huà)野馬情有獨(dú)鐘。這位國(guó)畫(huà)大師在法國(guó)進(jìn)修期間學(xué)習(xí)了馬的解剖,他花費(fèi)大量的時(shí)間觀察馬的動(dòng)態(tài)和表情。他非常喜歡畫(huà)蒙古馬,為后世留下了1000副素描繪畫(huà)珍品。 徐悲鴻畫(huà)的馬,有的飛奔,有的小跑,形態(tài)各異,非常有魅力。他畫(huà)的馬多是黑色,結(jié)合了中西方繪畫(huà)手法,線條和筆畫(huà)簡(jiǎn)單,但是每幅畫(huà)所畫(huà)的動(dòng)物卻都十分傳神。 徐悲鴻的畫(huà)與意大利傳教士郎世寧(Giuseppe Castiglione)(1688-1766)為清朝皇帝繪畫(huà)的八駿圖風(fēng)格迥異。這幅畫(huà)是全彩的,代表了歐洲油畫(huà)的風(fēng)格,與中國(guó)畫(huà)畫(huà)馬的風(fēng)格神似,但沒(méi)有徐悲鴻的畫(huà)中展示的能量與歡樂(lè)氛圍。 側(cè)重不同 也許很少有中國(guó)人知道希臘神話中關(guān)于飛馬珀加索斯(Pegasus)的故事。但是,人們“飛馬”這個(gè)詞匯并不陌生。一些牌子以“飛馬”命名,其中最有名的要數(shù)老牌子的飛馬香煙了。 西方的文學(xué)和藝術(shù)作品中有會(huì)說(shuō)話的馬和流淚的馬。在中國(guó),與馬相關(guān)的最多的要數(shù)語(yǔ)言詞匯了。這樣一來(lái),就馬而言,中國(guó)的文藝作品要比西方的蒼白得多。 但是,在談及此之前,我將會(huì)指明中西方側(cè)重的不同所在。換句話說(shuō),也就是中西方強(qiáng)調(diào)馬的方面不同。例如,大部分英語(yǔ)詞匯是根據(jù)年齡和性別來(lái)定義“馬”的。比如,小馬指的是4歲以下的公馬;小母馬指的是4歲以下的母馬;母馬指的是4歲或者4歲以上的母馬;一歲馬指的是年齡在1歲到2歲之間的馬;駒指的是1歲以下的馬。騸馬指的是去勢(shì)的馬,種馬是沒(méi)有去勢(shì)的馬。 相反,漢語(yǔ)中許多馬的描寫(xiě)與顏色有關(guān)。驃是黃色的馬;騮是帶有黑鬃和黑尾的紅色馬;骃是灰白色的馬;驪是黑色的馬;騧是有黑色馬嘴的黃色馬;騏是紫黑色的馬;驊是棗紅色的馬;骍是另外的一種紅馬;驄是藍(lán)色的馬;騅是帶有白蹄子的黑馬;駹是白面的黑馬。駒是年輕的馬,驥是年老馬。年輕或年老的具體程度不詳。駿是跑得快的馬,駑是跑得慢的馬。 不同的馬,名字不同。馬的名字要比十二生肖的名字多多了。但是,大部分馬是根據(jù)顏色命名的。 在中國(guó),與英文“prince charming”(白馬王子)相對(duì)應(yīng)的漢語(yǔ)詞是“騎白馬的王子”或者說(shuō)是“白馬王子”。關(guān)于白馬王子,還有個(gè)小小的童話故事。 但是,一項(xiàng)關(guān)于馬皮顏色的研究讓我感覺(jué)這個(gè)與迪斯尼童話故事有關(guān)的詞語(yǔ)頗具諷刺意味。隨著年齡的增長(zhǎng),出生時(shí)膚色較暗的馬會(huì)出人意料地變成灰色或者白色。如果你不相信,你可以看看白馬的馬皮。 因此,把一匹行將就木的白色老馬和一位王子相聯(lián)系,并不能表現(xiàn)王子的年輕和魅力。然而,既然我們大部分人都不是醫(yī)治馬的獸醫(yī),我們可以忽略掉白馬是老馬這個(gè)事實(shí),想象一下那象征純潔的白色吧,白馬王子是女性朋友的最佳伴侶。 文字記載 幾世紀(jì)的人馬互動(dòng),使得那些關(guān)于馬的詞匯代代傳承、豐富發(fā)展,它們體現(xiàn)了中國(guó)人對(duì)2014年馬年的態(tài)度。 馬除了作為軍隊(duì)英雄忠誠(chéng)和勇敢的化身外,還因?yàn)槠渥陨淼哪途眯允艿饺藗兊馁潛P(yáng)。諺語(yǔ)千里馬就體現(xiàn)了馬的耐久性。 或許,人和馬關(guān)系的最佳類(lèi)比跟伯樂(lè)有關(guān)。伯樂(lè)是能夠識(shí)別千里馬的人。在這里,人類(lèi)是人才的發(fā)掘者、支配者和訓(xùn)練者;馬是有待被發(fā)掘、培養(yǎng)的人才。很明顯,這是一個(gè)類(lèi)似于師徒的關(guān)系。 就此而論,馬也可能成為虎媽式嚴(yán)格教育方式的接受者,正如詞組“快馬加鞭”表現(xiàn)出的一樣。 但是,古代的中國(guó)人有認(rèn)同動(dòng)物的傾向。他們認(rèn)為人與動(dòng)物的聯(lián)系如此緊密,以致于當(dāng)他們談?wù)撟约厚R的時(shí)候也可能是在談?wù)撍麄冏约骸!癟o err is human(人非圣賢,孰能無(wú)過(guò))”這句話在漢語(yǔ)中對(duì)應(yīng)的句子是:“人有失足,馬有失蹄”。 一般,中國(guó)人拍馬屁的偏好,這種表示友好情誼的姿態(tài)已經(jīng)演變成為一種諂媚了。當(dāng)你拍得不當(dāng)?shù)臅r(shí)候,就拍到了馬腿上,那油腔滑調(diào)的諂媚以失敗告終了。 在這些諺語(yǔ)中,馬不再是人的仆人或者門(mén)徒了,而是欣賞的對(duì)象和權(quán)利的象征。馬的這種雙重含義也在中國(guó)人看待藝人的那些傳統(tǒng)觀念中體現(xiàn)出來(lái)。 人和馬的權(quán)力依賴(lài)關(guān)系因情形的不同而不同。驢子、騾子和馬這三種動(dòng)物里,馬居于最高等級(jí)。 在中國(guó)民間傳說(shuō)中,驢子和騾子通常被看作是馬的朋友,它們通常被用來(lái)襯托馬的偉大。馬總是作為好萊塢魔幻電影中的超級(jí)英雄出現(xiàn)。只有一次,馬的風(fēng)頭被駱駝蓋過(guò)了。在中國(guó)的傳說(shuō)里,駱駝的個(gè)頭比馬大,即使是最瘦的駱駝也比馬大。然而,駱駝從來(lái)沒(méi)有被譽(yù)為是征服世界的動(dòng)物。 毫無(wú)疑問(wèn),無(wú)論在古代還是現(xiàn)代,馬深受中國(guó)人的喜愛(ài)。但是,那些把“ma”(馬)作為姓氏的人與其他人相比,并不能以此證明有過(guò)人之處。 恰巧,中國(guó)的穆斯林把“穆罕默德”這個(gè)名字的讀音中國(guó)化,稱(chēng)為馬。從此之后,“馬”姓成為這一民族中的大姓。另外,因?yàn)樽置嬉馑嫉脑颍苌僦袊?guó)人名字叫“馬”,否則“王”就應(yīng)該是最受歡迎的名字了。 但是,即使是一位國(guó)王或者皇帝大概也要在馬背上鞏固江山大業(yè)。 相關(guān)閱讀 無(wú)免費(fèi)Wi-Fi成游客抱怨新問(wèn)題 蓋茨:會(huì)撿錢(qián) 愛(ài)刷碗 買(mǎi)飛機(jī) 美學(xué)者發(fā)明可視眼鏡 能清楚“看見(jiàn)”癌細(xì)胞 (中國(guó)日?qǐng)?bào)周黎明) |