|

查看原文

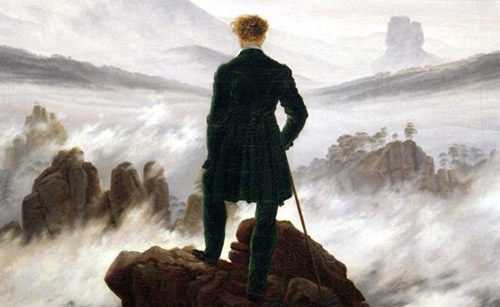

A number of recent books have lauded the connection between walking - just for its own sake - and thinking. But are people losing their love of the purposeless walk?

Walking is a luxury in the West. Very few people, particularly in cities, are obliged to do much of it at all. Cars, bicycles, buses, trams, and trains all beckon.

Instead, walking for any distance is usually a planned leisure activity. Or a health aid. Something to help people lose weight. Or keep their fitness. But there's something else people get from choosing to walk. A place to think.

Wordsworth was a walker. His work is inextricably bound upwith tramping in the Lake District. Drinking in the stark beauty. Getting lost in his thoughts.

Charles Dickens was a walker. He could easily rack up 20 miles, often at night. You can almost smell London's atmosphere in his prose. Virginia Woolf walked for inspiration. She walked out from her homeat Rodmell in the South Downs. She wandered through London's parks.

Henry David Thoreau, who was both author and naturalist, walked and walked and walked. But even he couldn't match the feat of someone like Constantin Brancusi, the sculptor who walked much of the way between his home village in Romania and Paris. Or indeed Patrick Leigh Fermor, whose walk from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul at the age of 18 inspired several volumes of travel writing. George Orwell, Thomas De Quincey, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bruce Chatwin, WG Sebald and Vladimir Nabokov are just some of the others who have written about it.

From recent decades, the environmentalist and writer John Francis has been one of the truly epic walkers. Francis was inspired by witnessing an oil tanker accident in San Francisco Bay to eschew motor vehicles for 22 years. Instead he walked. And thought. He was aided by a parallel pledge not to speak which lasted 17 years.

But you don't have to be an author to see the value of walking. A particular kind of walking. Not the distance between porch and corner shop. But a more aimless pursuit.

In the UK, May is National Walking Month. And a new book, A Philosophy of Walking by Prof Frederic Gros, is currently the object of much discussion. Only last week, a study from Stanford Universityshowed that even walking on a treadmill improved creative thinking.

Across the West, people are still choosing to walk. Nearly every journey in the UK involves a little walking, and nearly a quarter of all journeys are made entirely on foot, according to one survey. But the same study found that a mere 17% of trips were "just to walk". And that included dog-walking.

It is that "just to walk" category that is so beloved of creative thinkers.

"There is something about the pace of walking and the pace of thinking that goes together. Walking requires a certain amount of attention but it leaves great parts of the time open to thinking. I do believe once you get the blood flowing through the brain it does start working more creatively," says Geoff Nicholson, author of The Lost Art of Walking.

"Your senses are sharpened. As a writer, I also use it as a form of problem solving. I'm far more likely to find a solution by going for a walk than sitting at my desk and 'thinking'."

Nicholson lives in Los Angeles, a city that is notoriously car-focused. There are other cities around the world that can be positively baffling to the evening stroller. Take Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital. Anyone planning to walk even between two close points should prepare to be patient. Pavements mysteriously end. Busy roads need to be traversed without the aid of crossings. The act of choosing to walk can provoke bafflement from the residents.

"A lot of places, if you walk you feel you are doing something self-consciously. Walking becomes a radical act," says Merlin Coverley, author of The Art of Wandering: The Writer as Walker.

But even in car-focused cities there are fruits for those who choose to ramble. "I do most of my walking in the city - in LA where things are spread out," says Nicholson. "There is a lot to look at. It's urban exploration. I'm always looking at strange alleyways and little corners."

Nicholson, a novelist, calls this "observational"walking. But his other category of walking is left completely blank. It is waiting to be filled with random inspiration.

Not everybody is prepared to wait. There are many people who regard walking from place to place as "dead time" that they resent losing, in a busy schedule where work and commuting takes them away from home, family and other pleasures. It is viewed as "an empty space that needs to be filled up", says Rebecca Solnit, author of Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

Many now walk and textat the same time. There's been an increase in injuries to pedestriansin the US attributed to this. One study suggested texting even changed the manner in which people walked.

It's not just texting. This is the era of the "smartphone map zombie"- people who only take occasional glances away from an electronic routefinder to avoid stepping in anything or being hit by a car.

"You see people who don't get from point A to point B without looking at their phones," says Solnit. "People used to get to know the lay of the land."

People should go out and walk free of distractions, says Nicholson. "I do think there is something about walking mindfully. To actually be there and be in the moment and concentrate on what you are doing."

And this means no music, no podcasts, no audiobooks. It might also mean going out alone.

CS Lewis thought that even talking could spoil the walk. "The only friend to walk with is one who so exactly shares your taste for each mood of the countryside that a glance, a halt, or at most a nudge, is enough to assure us that the pleasure is shared."

The way people in the West have started to look down on walking is detectable in the language. "When people say something is pedestrian they mean flat, limited in scope," says Solnit.

Boil down the books on walking and you're left with some key tips:

Walk further and with no fixed route

Stop texting and mapping

Don't soundtrack your walks

Go alone

Find walkable places

Walk mindfully

Then you may get the rewards. "Being out on your own, being free and anonymous, you discover the people around you," says Solnit.

|

查看譯文

最近許多書都贊揚走路這一行為本身和思考的聯系。但是人們是否正逐漸對漫無目的的行走失去興趣?

走路在西方是件奢侈事。少有人會去步行,尤其是在城市里。汽車、自行車、公交車、電車和火車,這些都更吸引人。

走路反而通常是一種有計劃的休閑活動,或者是保健運動,是有助于減肥或保持健康的活動。但是人們還可以從步行中得到其它一些東西,一種思考的環境。

華茲華斯(Wordsworth)喜歡步行。他的工作讓他不可避免地要經常在湖區行走,在純粹質樸的美景中飲酒,沉浸到思考之中。

查爾斯?狄更斯(Charles Dickens)也喜歡走路。他可以很輕松地走完20英里,而且經常是在夜里。從他的文章中你幾乎可以嗅到倫敦的氣息。弗吉尼亞?伍爾夫(Virginia Woolf)為尋求靈感而行走,她從家鄉南唐斯的羅德麥爾出發,在倫敦的公園里漫步。

自然主義者、作家亨利?大衛?梭羅(Henry David Thoreau)則每天都在行走。但即使是他也無法做到康斯坦丁?布朗庫西(Constantin Brancusi)那樣的壯舉。布朗庫西是一位雕塑家,從羅馬尼亞的農村老家到巴黎這一路,他幾乎都是走著去的。更厲害的是帕特里克?萊斯?法莫(Patrick Leigh Fermor),他18歲時從荷蘭角港徒步到伊斯坦布爾,旅程給了他靈感,讓他寫出了好幾卷游記。喬治?奧威爾(George Orwell)、托馬斯?德?昆西(Thomas De Quincey)、納西姆?尼古拉斯?塔勒布(Nassim Nicholas Taleb)、弗里德里希?尼采(Friedrich Nietzsche)、布魯斯?查特文(Bruce Chatwin)、 溫弗里德?格奧爾格?澤巴爾德(WG Sebald)、弗拉基米爾?納博科夫(Vladimir Nabokov)也都寫過關于行走的文章。

近幾十年來,環保主義者、作家約翰?弗朗西斯(John Francis)可謂真正的英雄般的行者。弗朗西斯在舊金山港目睹一場油罐事故,受此影響22年來一直決絕乘坐機動車輛。所以,他步行,同時思考。他還發誓不開口說話,堅持了17年。

不過,要發現行走的價值,不一定要成為作家。一種特殊的行走方式,不是從家門口走到街角的商店,而是一種漫無目的的行動。

在英國,五月是全國步行月。弗雷德里克?格羅(Frederic Gros)教授的一本新書《行走的哲學》(A Philosophy of Walking)目前廣受關注。就在上周,斯坦福大學的一項研究顯示即使是在跑步機上走一走也能促進創新思維。

在整個西方,人們仍會選擇步行。一項調查表明,英國幾乎每一趟旅程都會包含一點步行的路程,近四分之一的旅程是完全徒步的。不過,該調查還發現17%的旅程就是“走路”,還包括遛狗。

“單純走路”這一類型深受創新思維者的喜愛。

“走路的速度和思考的節奏是相通的。走路需要一定的注意力,但是也給思考留下了很大的空間。我很相信一旦血液流經大腦,大腦就開始創造性地工作,”《消失的藝術:步行》(The Lost Art of Walking)的作者,杰夫?尼克爾森(Geoff Nicholson)說。

“你的感官變得敏銳。作為一名作家,我還把它當做一種解決問題的方式。出去走一走比只是坐在桌前‘冥思苦想’更有可能找到解決辦法。”

尼克爾森住在洛杉磯,這個城市出了名的車多。世界上有許多城市會讓走夜路的人很犯難,例如,馬來西亞首都吉隆坡。在相距很近的兩地走路也要很小心。人行道很神秘地就走到頭了。穿過繁忙的街道也沒有斑馬線。選擇步行會讓當地居民非常不解。“在很多地方,如果步行,你會覺得自己在進行一項有意識的活動,步行成了一種激進的行為,”《漫步的藝術:行走的作家》(The Art of Wandering: The Writer as Walker)的作者梅林?科弗利(Merlin Coverley)說。

但是即使在車水馬龍的城市,選擇漫步也會有所收獲。“我大多數都是在城市里,洛杉磯街頭異彩紛呈,”尼克爾森說。“有很多可以看的。這是城市探險。我常常去看小巷和街角。”

尼克爾森是位小說家,他稱這為“觀察式”步行。不過其它種類的步行還空缺著,等待靈感降臨時能補全。

但不是每個人都愿意等待。有許多人認為步行往返兩地是“停滯的時間”,他們不愿從忙碌的日程安排里耽擱這點時間,在他們忙碌的日程里,工作和上下班讓他們遠離了家庭和其它樂趣。步行被看做是“需要填補的空白,”《浪游之歌:走路的歷史》(Wanderlust: A History of Walking)的作者雷貝嘉?索爾尼(Rebecca Solnit)說。

現在許多人一邊走路一邊發短信。因為這個原因美國行人受傷率有所上升。一項研究顯示發短信甚至會改變人們走路的方式。

不僅僅是發短信。這是“智能手機地圖僵尸”的時代——人們偶爾從電子導航上抬頭看一眼,以防踩到什么東西或被車撞。

“不看手機人們就沒法從一個地方到另一個地方,”索爾尼說。“過去人們都會去主動了解一個地方。”

人們應該出去,不受干擾地行走,尼克爾森說。“我真的認為有用心行走這回事。此時此地,專注于你正做的事。”

這意味著沒有音樂,沒有播客,沒有有聲讀物。或許還指獨自行走。

克利夫?斯特普爾斯?劉易斯(CS Lewis)認為即使是說話也會破壞行走的過程。“走路時唯一的朋友是能夠完全分享你在鄉間行走時的每一個心境的體驗的人,一個眼神、一個停頓、或者至多輕碰一下就足夠確定我們同享這一樂趣。”

在西方,人們對走路的輕視在語言中也有跡可循。“人們說某樣東西‘pedestrian’,就是說它平淡無奇、很一般,”索爾尼說。

總結這些關于行走的書,可得出一些要點:

走遠一點,不要局限于一條路線

不要再發短信、看導航了

不要邊走邊聽有聲讀物

獨自出發

走可走的路

用心行走

那么你會得到回報。“獨自出發,自由自在、漫無目的地行走吧,去了解你周圍的人,”索爾尼說。

(譯者 巴黎的思不靈 編輯 丹妮)

掃一掃,關注微博微信

|